By now, the United States have just one offshore wind farm in operation: The 30 MW Block Island project off Rhode Island, which started generating in December 2016.

© Wikipedia/Ionna22, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

further informationFrom a slow start, the US offshore wind sector has reached take off point. State governments have raised their ambitions, while the extension of federal tax credits would underpin finance for the huge amount of offshore wind now in the US project pipeline. Just as it has tapped onshore wind, the US looks poised to reap the benefits of one its largest renewable energy resources.

At just over 97 GW of cumulative capacity at the end of first-quarter 2019, the US has more wind power installed than any other country in the world bar China. Wind is now the largest source of renewable energy in the US and, in 2018, provided 6.5% of the country’s electricity, according to the American Wind Energy Association.

However, the US has been very slow to take up the challenge of offshore wind. Offshore wind capacity in north west Europe has expanded rapidly and has more latterly taken root in China and Taiwan, but to date the US has just one offshore wind farm in operation, the 30 MW Block Island project off Rhode Island, which started generating in December 2016.

US wind developers focused first on onshore wind for the simple reasons that it was easier and cheaper to develop and good sites were available. Moreover, on the US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts, developers have a violent weather phenomenon to contend with which their European counterparts do not – hurricanes. These whirling maelstroms rarely make landfall, but their impacts out at sea demand new levels of ingenuity from offshore wind engineers.

Matching supply with demand

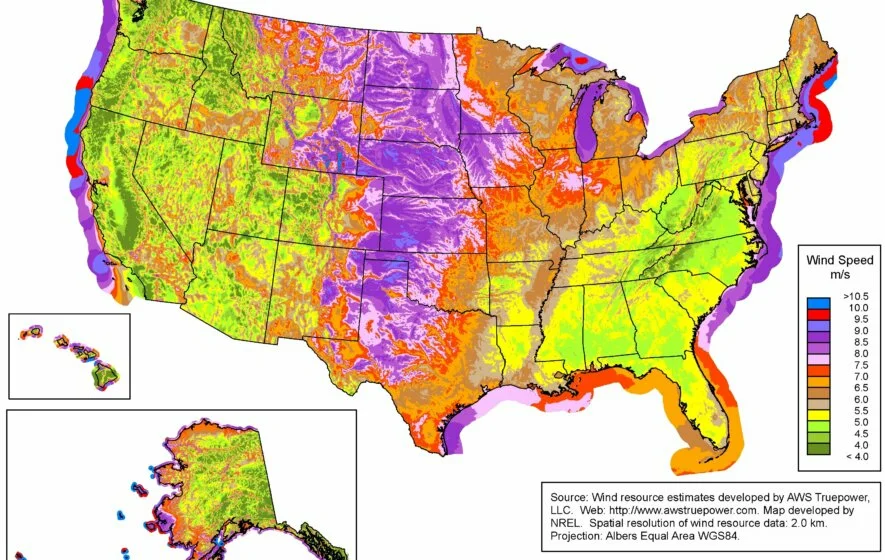

As a result, wind power in the US is geographically concentrated; Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa and Kansas account for more than half of US wind generation. These states have the strongest wind speeds, which are found in a band running north-south down the centre of the North American land mass.

The only other areas which can match the windiness of this central band are the country’s coasts and the Great Lakes area. These regions also account for 80% of US electricity demand, making a perfect match between onshore demand and potential supply from offshore wind.

The densely-populated US north east – New York area, Long Island and New England – also lack sufficient natural gas connections with the US’ prolific gas producing areas. When polar vortexes strike from the north, heating demand rises and infrastructure constraints on the gas grid have in recent years resulted in gas shortages at power stations. Offshore wind would diversify regional electricity supply, adding to supply security via low carbon electricity generation.

Moreover, the exploitable US offshore wind resource is big. With a stable policy framework in place, the US Department of Energy estimates that 22 GW of offshore wind could be installed by 2030 and 86 GW by 2050. Even this would barely scratch the surface of an estimated offshore power potential of more than 2,000 GW.

This is the technical resource potential, i.e. what could actually be built with today’s technology. It excludes low wind speed areas, water depths too deep for ground mounted foundations and areas already in use such as shipping lanes and marine protection areas.

Project pipeline builds

After a slow start, the US offshore wind industry now appears to be taking off. According to data compiled by RenewablesUK, the number of planned offshore wind projects in the US grew from 7.5 GW in 2018 to over 15.7 GW this year.

Wind rivals hydro as largest renewable energy source in the US

Source: BP Statistical Review of World EnergyRising ambition

This surge in activity and new level of confidence is being driven by a number of factors.

First, coastal state governments have stepped up their commitments to developing offshore wind. Massachusetts, for example, in 2018 extended a target of 1.6 GW offshore wind by 2027 to 3.2 GW by 2035. The state is particularly well suited for offshore wind because of the large acreage of shallow water extending off its coast.

New York has raised its offshore wind target to 2.4 GW by 2030 and New Jersey to 3.5 GW by 2030. Projects are also being developed in other states with supportive regulatory frameworks, such as Maryland, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Virginia.

Tax incentives provide support

Second, tax incentives are a key support for US offshore wind at a critical moment in the industry’s development. Two bills were introduced in the US Senate in June which seek to extend the 30% federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) for offshore wind, which would otherwise expire this year. The Offshore Wind Incentives for New Development Act proposes a six-year extension, while the Incentivizing Offshore Wind Power Act proposes eight years.

The expiry and renewal of ITCs has seen large up and down swings in renewable energy construction in the US. Expiry tends to create a short-term boom as developers rush to complete projects in time to take advantage of the ITC, while renewal provides a clear timetable for construction, which kickstarts development plans. Extending the ITC would be a big boon for the swathe of US offshore wind projects currently in the project pipeline.

Falling costs

Third, offshore wind costs are falling. In May last year, the 800 MW Vineyard Wind project off Massachusetts was the winner of the state’s first major offshore wind solicitation. The project developers agreed Power Purchase Agreements (PPA) at a record low of $74/MWh for the first year of generation from the project’s 400 MW Phase 1 and $65/MWh for the first year of Phase 2.

A PPA is a contract signed between the wind farm owners and the utilities that deliver the electricity to consumers. As with Vineyard wind, they typically last 20 years and are critical for project development. Once signed, banks will provide finance to developers, confident that the project has a secure revenue stream.

The PPAs for Vineyard Wind look highly competitive, but wind farm costs vary greatly, depending on factors such as turbine size, the wind resource, depth of water and distance from shore. This makes direct comparison of projects difficult, but the downward trajectory of overall costs is clear. Consultants Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimate that the cost of offshore wind has fallen 56% since 2010 to below $100/MWh with a particularly sharp drop of 24% in the last 12 months.

According to an independent study of the Vineyard Wind PPA carried out by the US’ National Renewable Energy Laboratory, when converted to a Levelised Revenue of Electricity figure (LROE), the PPAs for Vinyard Wind are comparable with new wind farms being built in northern Europe, which are also expected to come into operation in the early 2020s. This suggests that little risk premium is being attached to projects in the relatively undeveloped US offshore wind market.

LROE calculates the revenue the project can expect when factors such as state level renewable energy credits, tax break incentives and price escalation clauses are included, while the PPA prices are representative of the direct cost of the electricity to utilities.

The US also looks set to reap what could be called a ‘late mover’ advantage. Wind farm costs have fallen substantially in recent years in large part owing to the use of larger turbines. US developers will install turbines of 8 MW each and up for their first generation of offshore wind projects, each bigger than the already large 6 MW turbines deployed for Block Wind. In addition, they will benefit from improvements in turbine resilience which have allayed hurricane risk fears.