At present, the steel structure in the Hermann Barthel wharf in Derben, a village in Jerichow County in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, is a non-descript hull. But it is scheduled to receive innovative fittings and furnishings before year-end. A novel hybrid drive system will enable the channel push boat Elektra to start its trial runs in the first half of 2021, with a view to transporting heavy cargo between Berlin and Hamburg without generating emissions. The electric motors, which will be powered by hydrogen fuel cells and high-capacity lithium-ion batteries, will not emit carbon dioxide, soot or nitrous oxides, all of which are usually produced by the shipping sector in huge quantities.

“We’re the first to build this type of ship – and to this scale,” says project manager Professor Gerd Holbach of Berlin Technical University. Holbach is an expert in engineering and operating maritime systems and devised the 20-metre long and 8.2-metre wide channel push boat. Barges of this type push driveless boats, known as ‘lighters’. The advantage of this principle is increased flexibility: a push boat can convey several lighters and decouple them once they have reached their destination. This eliminates the long waits otherwise experienced during loading and unloading.

Innovative technologies unite

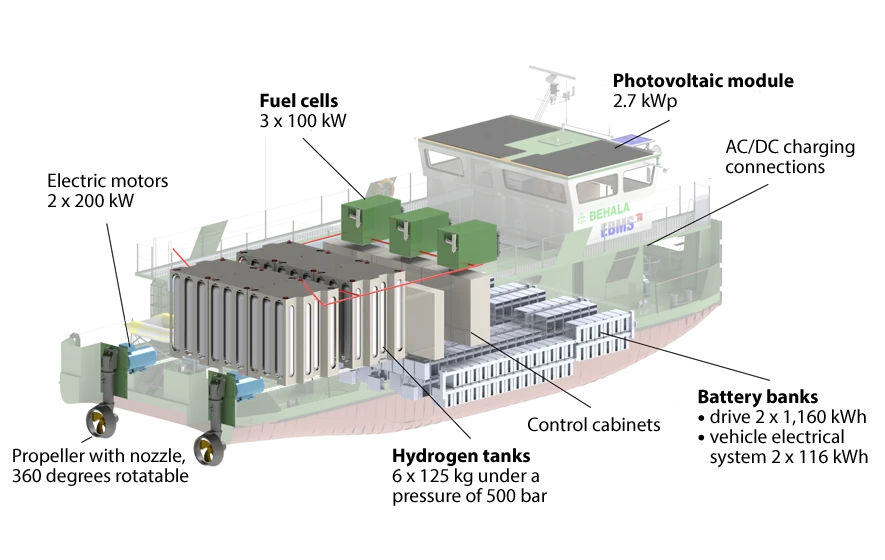

Elektra’s dual drives enable it to push up to 1,400 metric tons over 400 kilometres of river and canal waterways. In addition, the ship has two rear-mounted water-cooled electric motors, each rated at 200 kilowatts (kW). These are powered by three 100 kW fuel cells by Canadian manufacturer Ballard Power Systems. To supply them with hydrogen, the ship has six tanks from cleantech company Anleg Advanced Technology based in Wesel on the Lower Rhine containing a total of 750 kilogrammes of the fuel under a pressure of 500 bar. However, the hydrogen drive alone cannot propel the ship under full load. Elektra is thus additionally equipped with two battery banks by Dutch battery system specialist EST-Floattech with a combined capacity of 2.25 megawatt hours (MWh). These mammoth batteries alone weigh in at approximately 25 metric tons, accounting for some 15 percent of the push vessel’s total weight.

“Hydrogen is the main energy source and can handle normal operation. However, Elektra should be able to navigate short distances all electric,” declares Holbach. In this mode, it will be able to travel 65 kilometres in about eight hours. This would enable the ship to run purely on its batteries within Berlin, which is its envisaged home port. Moreover, the batteries can be activated whenever the ship requires additional power, for instance to reach higher speeds. “In hydrogen-only mode, we can achieve the same range and speed as a normal water vessel,” the professor emphasises. The push boat only runs out of steam after approximately 400 kilometres.

This covers the distance from the Hamburg Export Port to Berlin’s West Port, the domicile of the ship owner Berliner Hafen- und Lagerhausgesellschaft (BEHALA). Besides inner-city deployments, Elektra’s tasks will include transporting Siemens gas turbines from their production site in Germany’s capital to the Hanseatic city. It could also push wind turbines, bridge construction components and containers. Gerd Holbach and his team have a host of ideas and are planning a series of test drives to explore the boat’s possible uses.

Complementary energy systems

“With this project, we want to demonstrate the possibilities and reciprocal effects of the energy systems involved,” the project director says. This is why a second system will be installed: a small PV unit with 2.7 kW of peak capacity, which will charge the backup battery and supply a modest amount of power to the onboard electrical system, which will also be driven by two further 116 kWh batteries. Plans include setting up bunker stations along the route in order to charge the two main batteries and replenish the onboard hydrogen reserves. The first stations will be located in Berlin’s West Port and the Port of Lüneburg.

The hydrogen tanks can be swapped out while the two main batteries are charged – a procedure that takes several hours. This is faster than filling the tanks on site with the huge amounts of fuel needed. To avoid losing time, the procedure can occur during the nightly breaks required along the route. The engineers tested the concept by running model tests before construction work on the ship started in the Barthel wharf. The German Ministry of Transport is covering some of the construction costs as project partner. After all, since Elektra is a prototype, it is two to three times more expensive than a comparable diesel push boat. However, Holbach is convinced that costs would drop rapidly if it went into mass production.

Carbon-neutral thanks to green hydrogen and power

Operating costs are less easy to minimise. They are currently higher than those of diesel-powered vessels, at least if the hybrid ship is to navigate waters completely free of emissions. When running, it does not produce harmful emissions, as only water vapour is released into the atmosphere. However, pollutants are emitted when producing the electricity needed to power the push boat. To prevent this, the batteries have to be charged with 100% green electricity, which is generated from renewable sources.

Furthermore, the tanks would have to be filled with carbon-neutral hydrogen. One option is green hydrogen, which is obtained from water by hydrolysis. This process also requires electricity generated from renewables. Although this technology has already been researched thoroughly, only small pilot plants have been built thus far. Right now, it is much more expensive to produce green hydrogen than hydrogen from natural gas. Nevertheless, Gerd Holbach is confident that the technology will be profitable from 2025 onwards.

Some players are already following suit: Hamburg harbour ferry operator HADAG seeks to enlarge its fleet with three ferries featuring hybrid drives. The first step will involve the diesel engines being supplemented by batteries. In the second step, the diesel engines will be replaced by fuel cells. If the concept proves itself in day-to-day operations, it may represent a major step en route to decarbonising the shipping sector – made in Derben, Germany.