Modern-day wind turbines often extend over 200 metres into the sky, representing a potential obstacle for aviation. After all, the minimum safety height for aircraft in Germany is 150 metres. To ensure good pilot vision at night, they must have collision warning lights from 100 metres upwards. So far, these lights have usually flashed permanently, an irritant for many residents near onshore wind farms. But there is a solution to this.

Various techniques provide wind turbines with demand-driven night-time identification (DDNI) capabilities. This enables them to recognise approaching airplanes and helicopters, lighting up only when needed. This keeps the hazard light system from flashing otherwise. By the end of 2022, all of Germany’s onshore wind farms must be equipped with this feature, with the deadline for offshore wind turbines set at 31 December 2023. Based on current figures, nearly 30,000 wind turbines were in service at the end of 2021. While some operators have already retrofitted their assets, estimates have this still pending for some 14,000 turbines.

Transponder-based location technology

Aircraft can be located using transponder (secondary radar) technology. Airliners use transponders to communicate with each other. An on-board transmitter sends signals that are received and processed by other passenger airplanes. Lanthan Safe Sky, a company based in Walldorf in the state of Baden-Württemberg, engineered the world’s first NI that uses the TCAS system.

“We mount an air traffic receiver and antenna to the wind turbine that receives the signals emitted every second by aircraft to enable them to be located. The receiver forwards the signals to our nationwide server for evaluation. The server responds by transmitting switching signals, which the receiver sends on to the hazard light switching cabinet,” explains Gerd Möller, partner at Lanthan Safe Sky, summarising the inner workings of the DDNI system.

Over 98 percent idle time

Communication with the server occurs via the LTE network or a DSL connection in the turbine nacelle. However, not every turbine of a wind farm needs to be fitted with this technology. The traffic receiver is capable of receiving signals within a radius of up to ten kilometres and communicating with switch cabinets within the same perimeter. “In most cases, this enables us to achieve very long idle times. The lights stay switched off more than 98 percent of the time even in the vicinity of airports,” says Gerd Möller.

Other companies advertise similar idle times even when using primary radar for location purposes. To this end, the wind farm is equipped with sensors that broadcast radio waves and evaluate signals reflected by airplanes and helicopters to determine how far away they are. However, this technique reaches its limits when dealing with small aircraft.

Benefits for local residents and pilots

DDNI offers numerous advantages. “Clearly, the strongest USP is that it reduces light pollution significantly,” says Gerd Möller. He adds that while increasing acceptance among local residents, the system also makes sense from an environmental perspective. In addition, the expert states that since this smart technology had not yet become obligatory on introduction, some permits already related to DDNI deployment before it did.

Air traffic also benefits from collision warning lights not flashing all the time. “This means that pilots only see lights that are really important for them. This increases safety,” Möller explains, immediately citing another argument in favour of the system: “We believe that the signal lights’ current 20-year service life will double if they are not on permanently.”

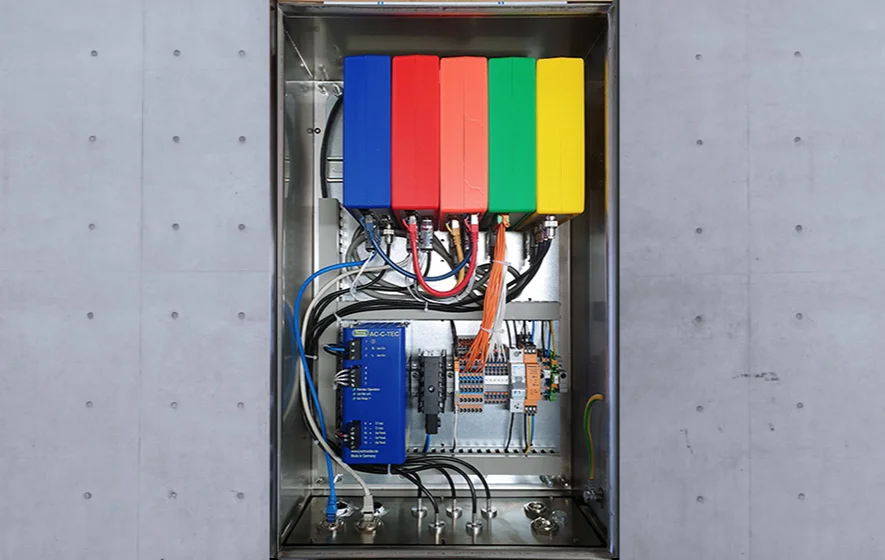

The companies which founded Lanthan Safe Sky claim that more than 12,000 traffic receivers have already been installed throughout Europe. The first transponder-based DDNI system has been running in the Wiemersdorf wind farm in Schleswig-Holstein for over ten years. Since then, the company has constantly refined the technology. “Now, the entire system fits in a 40-by-60 switch cabinet, and costs have dropped considerably,” says Möller.