Search

Frequent requests

Around 13 percent of the carbon dioxide emitted by the world transport sector, or approximately three percent of all global greenhouse gas emissions, is attributable to shipping. Granted, that may not be all that much, but if the global community is to achieve its climate goals, all sectors will have to toe the line. Even shipping.

Ship exhaust fumes are considered to be particularly noxious and harmful to the environment. Before now, shipping companies have almost exclusively relied on heavy fuel oil for propulsion. Compared to petrol or diesel exhaust gases, HFO fumes contain more nitrogen oxides, sulphur oxides and other pollutants. For this reason, inland shipping often turns to its lower-emission pendant – marine diesel oil. However, not only environmental associations, but also local residents of ports and waterways are calling for shipping to become cleaner.

Ideas for alternative ship engines abound and whilst some concepts require more research, others have long since left the drawing board and are being put to good use on the high seas. For example, some shipping companies have adapted their vessels to run on alternative fuels. Others have opted to revisit the origins of seafaring and take advantage of ocean winds. Although, those talking of a return to the sailing age are surely mistaken …

Bildinformationen:

LNG, i.e. liquefied natural gas, is a hot topic when it comes to HFO alternatives. Ships don’t need to be refitted with new engines in order to run on LNG and less CO2 is emitted during combustion. Norway is pioneering this technology as, according to the Norwegian classification society DVN GL, out of the 163 LNG vessels which were in operation across the globe in June 2019, 65 operated mainly in Norway in comparison to the 44 which set sail in Europe and only eleven in international waters. One such international ship is the AIDAnova (picture). Commissioned in late 2018 by the US-British shipping company Carnival, it is the world's first LNG-only cruise ship and at 337 meters long, it is also likely to be one of the largest LNG-powered ships in the world. LNG offers huge prospects: DNV GL estimates that liquid gas will account for one-third of the energy mix used in shipping by 2050 (© AlanMorris, shutterstock.com).

Bildinformationen:

According to Swedish company Stena Line, the ‘Stena Germanica’ is the first ferry in the world with a methanol engine. The fuel is generated using wood, biogas or carbon dioxide. RWE has being running a plant which synthesises methanol using CO2 from power plant fumes since 2019. In fact, it is even possible for methanol to be emission-neutral if carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is used and the synthesis is powered by green electricity. Stena Line's sustainability report also lists other ways in which to operate with lower emissions: Clean hulls and artificial intelligence on board should reduce consumption and in many ports, ships could use electricity produced sustainably on land instead of generating it with their engines. The shipping company is now testing a hybrid drive on the ‘Stena Jutlandica’, where a battery reduces the consumption of its engines during harbour manoeuvres. In the medium term, the ship is to traverse the 50 nautical miles between Frederikshavn and Gothenburg fully electrically (© Stena Line).

Bildinformationen:

German wind turbine manufacturer Enercon has been transporting the components of offshore turbines with its ‘E-Ship 1’ since 2008. The 130-meter-long ship is powered by two diesel generators which, according to Enercon, are fired exclusively using low-emissions marine diesel oil instead of heavy fuel oil. The electricity generated in this way also operates four Flettner rotors. The rotating cylinders use a certain flow phenomenon, known as the ‘Magnus effect’, to convert wind power into propulsion. According to Enercon, this saves around 15 percent of fuel under favourable conditions. Although the concept was originally developed about 100 years ago by the German Anton Flettner, in 2018 the Finnish ferry Viking Grace was equipped with a Flettner rotor in addition to an LNG engine (© Jan Oelker / Enercon).

Bildinformationen:

However, there are easier ways to use wind as a driving force. Hamburg-based company SkySails Group is building towing kites which can be harnessed to ships. Although this method only works with tailwind, it is surprisingly effective: “With good wind, it is possible to halve the vessel’s fuel consumption by using the towing kite,” SkySails told en:former. Perhaps the biggest advantage, however, is that ships can be relatively easily retrofitted with the auxiliary drive. The 90-meter-long mini-bulk carrier ‘Michael A.’ (pictured) is equipped with a 160-square-meter kite. According to the company, SkySails' largest towing kite measures 400 square meters (© SkySails Group).

Bildinformationen:

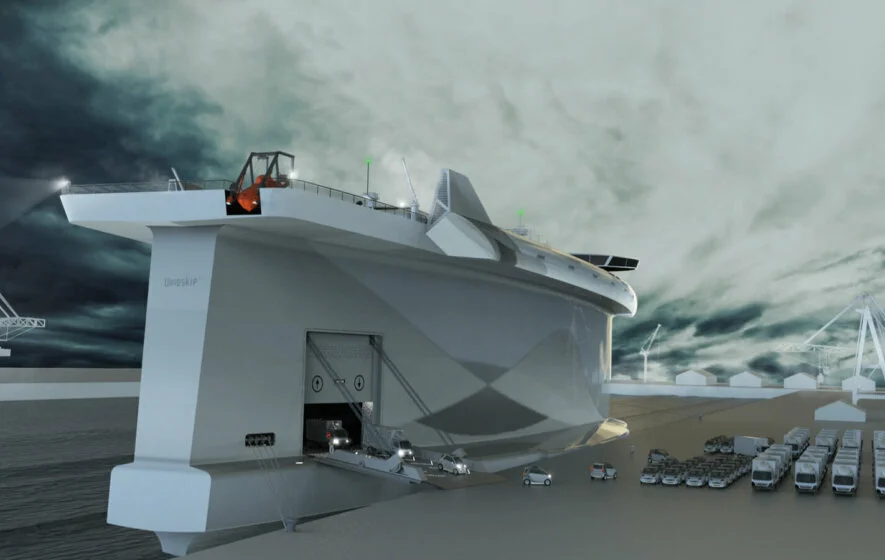

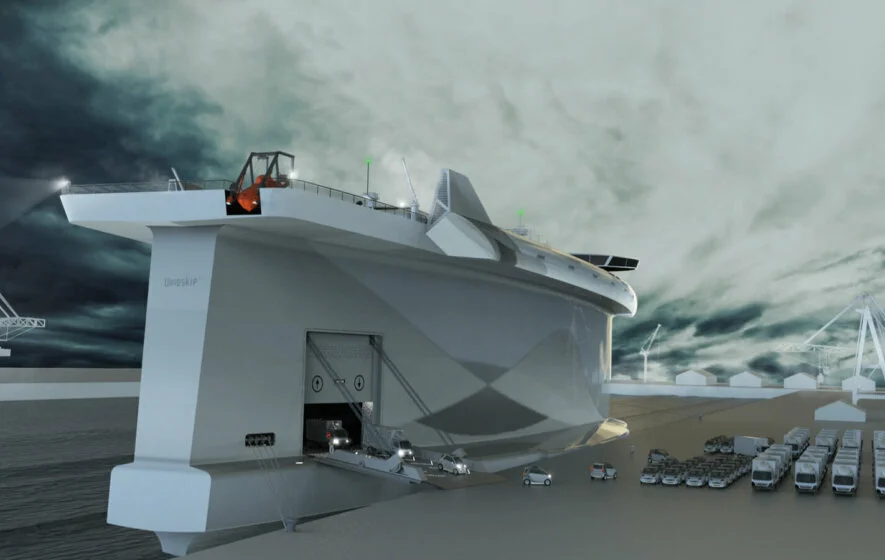

Bring the tradition of sailing into the 21st century – nobody is taking this idea as seriously as Norwegian Terje Lade with his ‘Vindskip®’. The entire hull is formed like a symmetrical aircraft wing. Once the LNG engine has brought the ship up to speed, it can largely maintain its pace using wind power, even if the wind hits the ship from the front at a diagonal angle. Preliminary model tests are said to have proven successful, but the 200-meter version is yet to be made a reality. “Currently we are conducting final tests and validation, in order to document fuel consumption” , Lade explained to en:former. This is important for investors. It won’t be easy to convince them, as it just sounds a bit too good to be true: 60 percent fuel savings and 80 percent less emissions than similar ships (© Lade AS).

German wind turbine manufacturer Enercon has been transporting the components of offshore turbines with its ‘E-Ship 1’ since 2008. The 130-meter-long ship is powered by two diesel generators which, according to Enercon, are fired exclusively using low-emissions marine diesel oil instead of heavy fuel oil. The electricity generated in this way also operates four Flettner rotors. The rotating cylinders use a certain flow phenomenon, known as the ‘Magnus effect’, to convert wind power into propulsion. According to Enercon, this saves around 15 percent of fuel under favourable conditions. Although the concept was originally developed about 100 years ago by the German Anton Flettner, in 2018 the Finnish ferry Viking Grace was equipped with a Flettner rotor in addition to an LNG engine (© Jan Oelker / Enercon).

However, there are easier ways to use wind as a driving force. Hamburg-based company SkySails Group is building towing kites which can be harnessed to ships. Although this method only works with tailwind, it is surprisingly effective: “With good wind, it is possible to halve the vessel’s fuel consumption by using the towing kite,” SkySails told en:former. Perhaps the biggest advantage, however, is that ships can be relatively easily retrofitted with the auxiliary drive. The 90-meter-long mini-bulk carrier ‘Michael A.’ (pictured) is equipped with a 160-square-meter kite. According to the company, SkySails' largest towing kite measures 400 square meters (© SkySails Group).

Bring the tradition of sailing into the 21st century – nobody is taking this idea as seriously as Norwegian Terje Lade with his ‘Vindskip®’. The entire hull is formed like a symmetrical aircraft wing. Once the LNG engine has brought the ship up to speed, it can largely maintain its pace using wind power, even if the wind hits the ship from the front at a diagonal angle. Preliminary model tests are said to have proven successful, but the 200-meter version is yet to be made a reality. “Currently we are conducting final tests and validation, in order to document fuel consumption” , Lade explained to en:former. This is important for investors. It won’t be easy to convince them, as it just sounds a bit too good to be true: 60 percent fuel savings and 80 percent less emissions than similar ships (© Lade AS).

LNG, i.e. liquefied natural gas, is a hot topic when it comes to HFO alternatives. Ships don’t need to be refitted with new engines in order to run on LNG and less CO2 is emitted during combustion. Norway is pioneering this technology as, according to the Norwegian classification society DVN GL, out of the 163 LNG vessels which were in operation across the globe in June 2019, 65 operated mainly in Norway in comparison to the 44 which set sail in Europe and only eleven in international waters. One such international ship is the AIDAnova (picture). Commissioned in late 2018 by the US-British shipping company Carnival, it is the world's first LNG-only cruise ship and at 337 meters long, it is also likely to be one of the largest LNG-powered ships in the world. LNG offers huge prospects: DNV GL estimates that liquid gas will account for one-third of the energy mix used in shipping by 2050 (© AlanMorris, shutterstock.com).

According to Swedish company Stena Line, the ‘Stena Germanica’ is the first ferry in the world with a methanol engine. The fuel is generated using wood, biogas or carbon dioxide. RWE has being running a plant which synthesises methanol using CO2 from power plant fumes since 2019. In fact, it is even possible for methanol to be emission-neutral if carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is used and the synthesis is powered by green electricity. Stena Line's sustainability report also lists other ways in which to operate with lower emissions: Clean hulls and artificial intelligence on board should reduce consumption and in many ports, ships could use electricity produced sustainably on land instead of generating it with their engines. The shipping company is now testing a hybrid drive on the ‘Stena Jutlandica’, where a battery reduces the consumption of its engines during harbour manoeuvres. In the medium term, the ship is to traverse the 50 nautical miles between Frederikshavn and Gothenburg fully electrically (© Stena Line).

German wind turbine manufacturer Enercon has been transporting the components of offshore turbines with its ‘E-Ship 1’ since 2008. The 130-meter-long ship is powered by two diesel generators which, according to Enercon, are fired exclusively using low-emissions marine diesel oil instead of heavy fuel oil. The electricity generated in this way also operates four Flettner rotors. The rotating cylinders use a certain flow phenomenon, known as the ‘Magnus effect’, to convert wind power into propulsion. According to Enercon, this saves around 15 percent of fuel under favourable conditions. Although the concept was originally developed about 100 years ago by the German Anton Flettner, in 2018 the Finnish ferry Viking Grace was equipped with a Flettner rotor in addition to an LNG engine (© Jan Oelker / Enercon).

However, there are easier ways to use wind as a driving force. Hamburg-based company SkySails Group is building towing kites which can be harnessed to ships. Although this method only works with tailwind, it is surprisingly effective: “With good wind, it is possible to halve the vessel’s fuel consumption by using the towing kite,” SkySails told en:former. Perhaps the biggest advantage, however, is that ships can be relatively easily retrofitted with the auxiliary drive. The 90-meter-long mini-bulk carrier ‘Michael A.’ (pictured) is equipped with a 160-square-meter kite. According to the company, SkySails' largest towing kite measures 400 square meters (© SkySails Group).

Bring the tradition of sailing into the 21st century – nobody is taking this idea as seriously as Norwegian Terje Lade with his ‘Vindskip®’. The entire hull is formed like a symmetrical aircraft wing. Once the LNG engine has brought the ship up to speed, it can largely maintain its pace using wind power, even if the wind hits the ship from the front at a diagonal angle. Preliminary model tests are said to have proven successful, but the 200-meter version is yet to be made a reality. “Currently we are conducting final tests and validation, in order to document fuel consumption” , Lade explained to en:former. This is important for investors. It won’t be easy to convince them, as it just sounds a bit too good to be true: 60 percent fuel savings and 80 percent less emissions than similar ships (© Lade AS).

LNG, i.e. liquefied natural gas, is a hot topic when it comes to HFO alternatives. Ships don’t need to be refitted with new engines in order to run on LNG and less CO2 is emitted during combustion. Norway is pioneering this technology as, according to the Norwegian classification society DVN GL, out of the 163 LNG vessels which were in operation across the globe in June 2019, 65 operated mainly in Norway in comparison to the 44 which set sail in Europe and only eleven in international waters. One such international ship is the AIDAnova (picture). Commissioned in late 2018 by the US-British shipping company Carnival, it is the world's first LNG-only cruise ship and at 337 meters long, it is also likely to be one of the largest LNG-powered ships in the world. LNG offers huge prospects: DNV GL estimates that liquid gas will account for one-third of the energy mix used in shipping by 2050 (© AlanMorris, shutterstock.com).

According to Swedish company Stena Line, the ‘Stena Germanica’ is the first ferry in the world with a methanol engine. The fuel is generated using wood, biogas or carbon dioxide. RWE has being running a plant which synthesises methanol using CO2 from power plant fumes since 2019. In fact, it is even possible for methanol to be emission-neutral if carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is used and the synthesis is powered by green electricity. Stena Line's sustainability report also lists other ways in which to operate with lower emissions: Clean hulls and artificial intelligence on board should reduce consumption and in many ports, ships could use electricity produced sustainably on land instead of generating it with their engines. The shipping company is now testing a hybrid drive on the ‘Stena Jutlandica’, where a battery reduces the consumption of its engines during harbour manoeuvres. In the medium term, the ship is to traverse the 50 nautical miles between Frederikshavn and Gothenburg fully electrically (© Stena Line).

German wind turbine manufacturer Enercon has been transporting the components of offshore turbines with its ‘E-Ship 1’ since 2008. The 130-meter-long ship is powered by two diesel generators which, according to Enercon, are fired exclusively using low-emissions marine diesel oil instead of heavy fuel oil. The electricity generated in this way also operates four Flettner rotors. The rotating cylinders use a certain flow phenomenon, known as the ‘Magnus effect’, to convert wind power into propulsion. According to Enercon, this saves around 15 percent of fuel under favourable conditions. Although the concept was originally developed about 100 years ago by the German Anton Flettner, in 2018 the Finnish ferry Viking Grace was equipped with a Flettner rotor in addition to an LNG engine (© Jan Oelker / Enercon).

photo credit: MD_Photography, shutterstock.com