Tens of thousands of green electricity producers have thrown a spanner in the works, or rather the supply networks. Grid operators have their work cut out for them trying to integrate their services sensibly and efficiently. Whilst operators are able to control the fluctuating input of wind and solar farms, when necessary, this becomes nigh-on impossible when it comes to the countless private small and micro plants. Even virtual power stations that specialise in combining and coordinating small power generators and consumers are only equipped to accommodate producers of a certain scale.

Nevertheless, a solar system on one’s roof can still very much be worth the hassle, depending on where you live. In Germany, for example, according to the Renewable Energy Act, you are remunerated for electricity which you feed into the grid – for 20 years following installation. And by then, most photovoltaic systems will have already paid for themselves. But how does one turn a profit with a PV system when living in a country without such subsidies? And how can these systems be used to stabilise the power grids?

Security gaps in measuring systems

“Smart meters (in German) facilitate individual bi-directional data transfers, thereby paving the way for new business models and enabling the integration of decentralised energy supply,” says Christoph Burger of the European School of Management and Technology (ESMT) in Berlin. When it comes to power generation, these smart meters are able to record how much electricity is generated and where it flows to, i.e. into one’s own household, to the neighbours or into the public grid – and they’re pretty precise. But the reverse is also possible: the origin of the electricity is also detectable. Burger does, however, highlight some limitations: “The current communication protocols of smart meters pose a security risk.”

Today’s systems are relatively susceptible to hacker attacks, as Burger and two colleagues established in a study conducted by the German Energy Agency (dena). This not only poses a risk to the data security of producers and consumers, it also means that measuring systems can be manipulated – thus facilitating fraud, for example. Transmissions of erroneous data, however, present a far greater problem: Hackers could destabilise the public power grid by transmitting false information -– thereby triggering a blackout. The answer to all these issues comes in the form of a technology that most people are already familiar with, albeit in a different context: Blockchain.

The digital notary

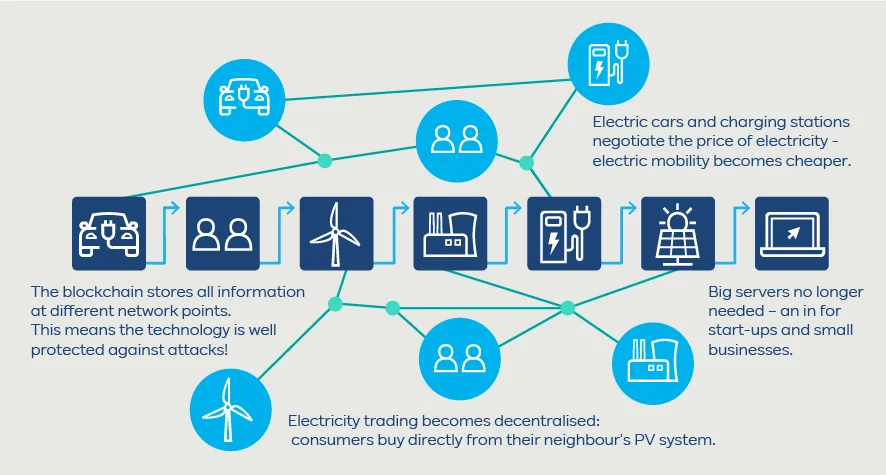

This technology first showed up on international radars in relation to Bitcoin and other crypto currencies. But this is only one of its many conceivable uses. Blockchain is also referred to as ‘distributed ledger technology’ , DLT for short, and the two are often used synonymously. What all DLTs have in common is that they decentrally store multiple copies of data packets in order to protect information from being tampered with.

With blockchain, each new piece of information is appended as an additional data block, thereby creating a blockchain. Additionally, any change or (rather) extension of a blockchain is documented in every copy. Attempts to tamper with an individual copy would be exposed, as they would deviate from the other copies. In this way, there is endless independent digital evidence of deposited information.

Explainer video: What exactly is the Blockchain and what is it good for?

Reduced transaction costs

The thing that makes this technology so revolutionary is that there is no single central location where information has to be authenticated or managed: “Blockchain is a decentralised transaction technology that facilitates end-to-end data transparency,” explains Burger. As regards crypto currencies, blockchains are thus able to replace banks. When buying a house, they could be used to replace the need for a notary because they are more reliable than any notarial deed.

Blockchain and other DLTs have long been considered an option for decentralised electricity trading in the energy industry. Domestic solar systems could use this technology to document their feed-ins and – instead of receiving a lump-sum payment from the grid operator – sell the electricity to a customer in real time. Distributing electricity on such a minor scale with a power exchange or via the local provider quickly becomes unprofitable due to the margins of traders and suppliers. However, the combination of smart meters and blockchains would eliminate these transaction costs. The aim is, for example, for the solar system of one market participant to communicate directly with a power storage device – perhaps the battery of an electric car.

Manage balancing cycles per blockchain

For the grid operator, this would have the advantage that the feed-in and withdrawal of electricity would be better balanced. This would mean fewer fluctuations in terms of grid frequency, which the network operator would have to compensate for using (expensive) operating reserve.

Large electricity producers and traders are already forced to ensure that the electricity sold is equal to the electricity generated or rather acquired. This balance must be equalised once every 15 minutes. The grid operators coordinate the balancing of fluctuations outside this ‘balancing cycle’.

As such, blockchain electricity trading would not only be in the interests of the smallest producers. Biogas plants, solar and wind farms, large CHP plants and, in theory, large power plants could also sell their electricity in real time in this way.

In practice, things are progressing

The potential of this technology has been the topic of discussion for several years now. And now these theories are increasingly being made a reality. Wuppertal’s municipal utility uses blockchain to connect its electricity customers with local producers. The Australian company Power Ledger is implementing various pilot projects across Australia, Japan, Thailand and the US, while Austria’s second largest city, Graz, is also looking to introduce the technology, after an initial test phase where ten households are able to sell their solar power to their neighbours using blockchain.

So, do we have the answer? Yes and no, is the conclusion drawn by Christoph Burger and his colleagues: “The public blockchain is still too slow, energy-intensive and inconvenient to be used in today’s smart meters.” But things are progressing. A regulatory framework is also needed. At the end of the day, the same goes for DLT-based electricity trading as is does for all network technologies: Things only start to get really interesting when they reach a certain scale.

Photo credits: Pushish Images, shutterstock.com