An acceleration in coal plant closures in Chile marks a milestone in the country’s changing energy mix, which has seen many twists and turns over the past 20 years. From gas dependence to coal and back again, the country now looks set to leave fossil fuels behind.

Goodbye to coal

The past five years have seen a rapid acceleration in the deployment of new renewable energy capacity, which is allowing Chile’s coal plants to be phased out quicker than expected. The 128-MW Bocamina 1 coal-fired plant will close two years earlier than planned, while owner Enel is seeking authorisation to close the 350-MW Bocamina 2 plant in May 2022. In addition, the AES-operated 120-MW Ventanas 1 has closed and the 220-MW Ventanas 2 plant will also shut in May 2022, ahead of schedule.

The government now expects 11 coal-fired units to come offline by 2024, rather than the previously planned eight, with the eventual goal of phasing out all 5.5 GW of the country’s coal-fired generation by 2040.

No return to gas

Hydropower has historically been the backbone of the Chilean electricity system supported by a growing proportion of fossil fuels. Up until the mid-2000s, gas was imported from Argentina. However, as Argentina’s gas balance fell into deficit, these imports dried up and Chile turned more to coal, only to revive gas use when LNG imports started in 2009. In 2018, Argentina resumed gas exports to Chile after a 12-year hiatus. Even so, Chilean consumption of fossil fuels for power generation has fallen since 2016, owing to the rise of new renewable energy sources. In 2019, wind and solar power provided 10.9 TWh of power in addition to 10.0 TWh from geothermal and biomass. Together with 20.9 TWh of hydropower, renewable energy fell just shy of meeting 50% of the country’s electricity demand, a significant increase over the decade in which total electricity generation rose 37% to 83.9 TWh.

New renewable energy sources attracted cumulative investment of $14.8 billion between 2010-19 with their share of installed capacity rising from 5% in 2014 to 23% by May 2020. Falling costs for wind and solar power, along with Chile’s substantial resources of both, suggest renewables will gradually push fossil fuel power generation out of the energy mix, allowing the country to meet its climate change targets.

Development of the Chilean power generation

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2020Chilean geography

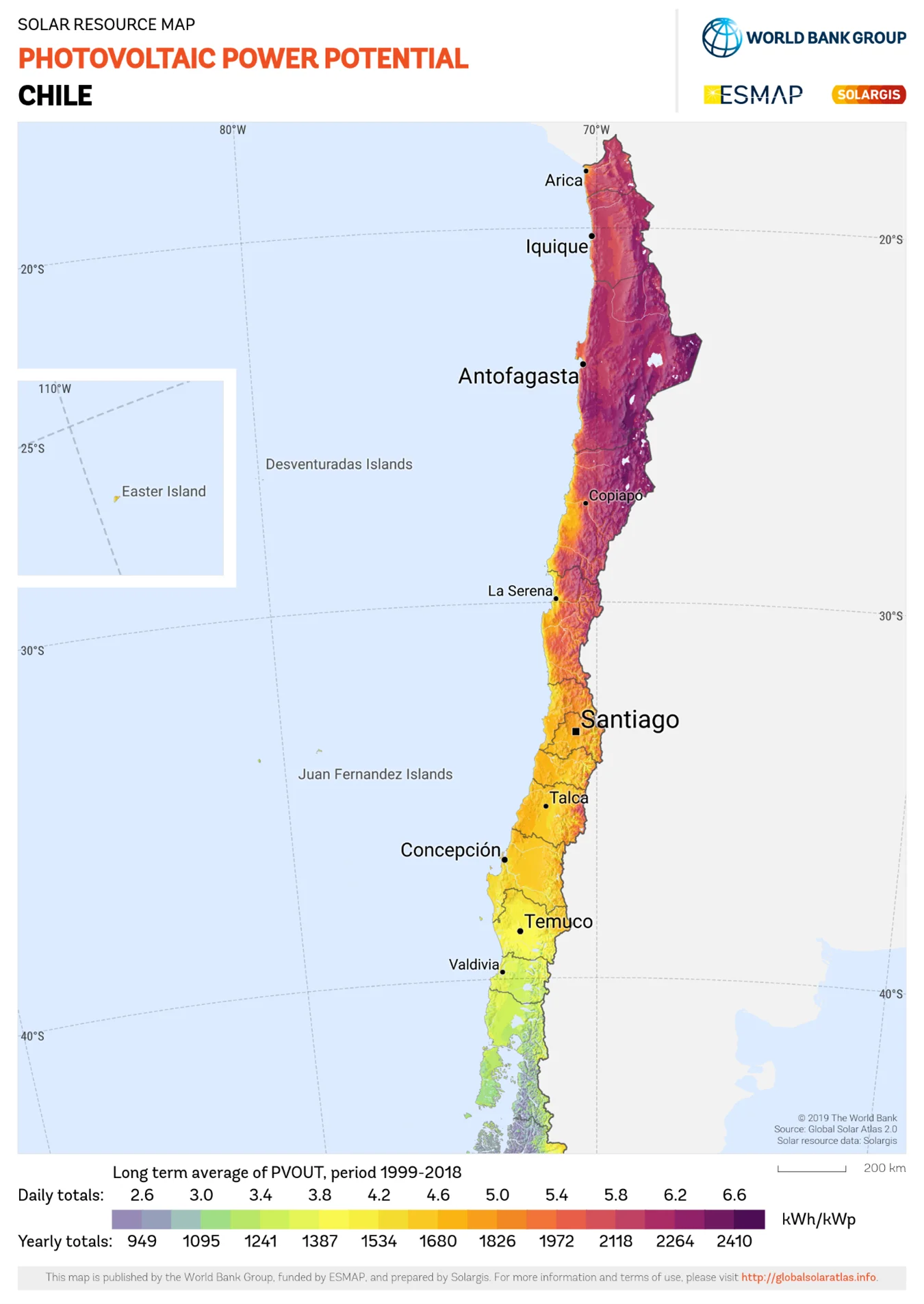

Chile’s geography provides both renewable energy options and challenges. The country‘s greatest solar resource lies in its far north in the Atacama Desert, which has solar power potential of 9 kWh/m2 a day, the highest in the world, although the economically-viable solar resource stretches far down the country to south of the capital Santiago.

Chile also has an extensive coastline providing numerous onshore wind sites with good wind speeds, although the best are found in the remote Patagonian region in the country’s far south. However, even up into the north the Global Wind Atlas shows mean wind speeds of 8 meters per second and above. Solar generation in the north is perfectly positioned to supply energy to the country’s mining operations, but it is also far from the country’s main population centre Santiago. Chile is long and thin stretching 4,270 kilometres from north to south, while averaging only 177 km east to west. Its electricity system has evolved around four separate grids, SEM and SEA in the south, SIC in the centre and SING in the north. Transmission capacity has been the key to unlocking the renewable resources of the north.

Major developments were the completion in November 2017 of a new $700 million interconnector, the 600-km TEN line, between the SING and SIC grids, followed by the commissioning of the 753km Polpaico-Cardones line in June 2019, allowing the two grids to operate as a single system, now known as the National Electric System (SEN), which serves over 90% of electricity demand. The new interconnections reduced grid congestion and allowed renewable electricity to flow south. It also had the effect of raising prices for northern power generators, who had seen wholesale prices sink to zero at some times of the day, owing to regionally-restricted surplus solar power generation.

Policy framework

Chile has a common view on renewable energy that transcends governments. Renewable energy in Chile’s long deregulated electricity market has been supported by a strong policy framework. From 2013, the government required utilities with up to 200 MW of capacity to meet 20% of their contractual obligations from renewable sources by 2025. In addition, in 2014, the government reformed its tendering system for power procurement to allow generators to bid for specific ‘time blocks’, a system designed to encourage the development of variable generation.

In 2017, a carbon levy came into effect, placing a $5/metric ton price on carbon dioxide emissions for power plants of 50 MW or larger, again helping to tilt the economics of power generation in renewables’ favour. Moreover, to support small roof top solar systems, excess generation from households is sold back to the grid at the retail price of electricity.

In the most recent tenders for power generation, all available capacity has been met by renewables with one Atacama Desert project in 2017 offering power at just $21.5/MWh. According to a study, Decarbonisation Tradeoffs: A Dynamic General Equilibrium Modelling Analysis for the Chilean Power Sector, published in October 2020, as of 2019, 33 GW of new renewable energy projects had received environmental approval, more than the current capacity of the whole power system.

Rising ambition

As a result, the government has been emboldened to set more ambitious targets. The National Energy Policy 2050 sets a goal of meeting 60% of the country’s electricity generation with renewables by 2035 and 70% by 2050.

Chile also hopes to achieve substantial transport electrification, targeting 40% electric vehicles by 2050 and 100% electric buses. This will further raise demand for power, requiring more renewable energy capacity to be installed, one effect of which is likely to be a growing need for energy storage to meet the increased variability of generation within the system. Moreover, in November, the government presented a National Green Hydrogen Strategy, which aims to make use of the country’s prolific renewable solar and wind resources to produce green hydrogen.

The strategy targets 5 GW of electrolyser capacity as early as 2025 and the production of the world’s cheapest green hydrogen by 2030. The government sees this as a potential export industry as well as a domestic support for the country’s own energy system. It has set a goal of becoming one of the top three exporters of hydrogen by 2040. If Chile can achieve this goal it would add to an export profile well suited to the global energy transition. The country is the world’s largest producer of copper, a commodity essential to electrical systems, and has the world’s largest copper reserves. It is also the second largest producer of lithium, used for electric vehicle and electricity storage batteries, and has the world’s largest reserves of the metal.