It was only at the beginning of the year that the German Hydrogen Council called for an ambitious hydrogen strategy designed to give the EU a hydrogen economy capable of competing on a global scale. Mario Ragwitz, spokesperson of the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft Hydrogen Network, believes that this requires local construction: “We need to adopt a European mindset, above all to coordinate relevant infrastructure. At the same time, however, one must pool expertise at the regional level with a view to attaining critical mass at locations where such investments are worthwhile.”

Innovative hydrogen industry resides in Eastern Germany

As Director of the Fraunhofer Institute for Energy Infrastructure and Geothermal Energy (IEG), Ragwitz has contributed to several studies concerning Eastern Germany’s hydrogen economy. One such publication is the East German H2 Masterplan (Link in German), which was devised by several Fraunhofer institutes on commission from Leipzig-based VNG AG. The study’s authors conclude that “the new German states are home to numerous highly specialised and world-renowned mechanical and plant engineering companies along with leading hydrogen and fuel cell research institutes.”

For instance, Dresden-based plant engineering firm Sunfire is developing and creating various methods of producing hydrogen and syngas. Sunfire claims to have built the world’s largest high-temperature electrolyser (Link in German), with a capacity of 2.6 megawatts (MW), in a refinery in Rotterdam, Netherlands. The company is in the process of installing a 10 MW pressure-alkali electrolyser at RWE’s Emsland gas-fired power station. It was only in March that the company commenced serial production of this technology. Some components will be sourced from a plant belonging to automotive supplier Vitesco near Chemnitz, Germany.

Huge potential for renewable energy

Expert Ragwitz claims that Eastern Germany also lends itself as a site on which to produce hydrogen: “Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg in particular have made substantial progress in green electricity generation.”

Thanks to the Baltic Sea coast, large parts of north Germany’s flatlands, and fairly sparse population, conditions in the northern area states favour wind power production. Low-cost green energy is a major prerequisite for a competitive hydrogen economy, as huge amounts of this electricity are required for sustainable production of pure hydrogen.

The future of former mining areas

Decommissioned mining sites are also to play a central role in generating clean electricity and producing green hydrogen. “The Lusatian mining region is very big and can be developed at a manageable cost,” Ragwitz believes. As many as seven gigawatts (GW) of renewable generation capacity, including wind and solar farms, are envisaged to be installed on this land, which covers approximately 33,000 hectares.

Spanning 33,000 hectares, the discontinued mining premises in Lusatia are about 1.5 times the size of the Rhenish lignite mining region, where land is already being used to produce renewable energy. Midway through 2023, in cooperation with the Julich Research Centre, RWE will commence construction of a demonstration facility which will combine sustainable electricity generation with agriculture on greenfielded areas of the Garzweiler opencast mine.

This could be a way of repurposing land after the discontinuation of lignite extraction scheduled for 2030. Green energy from the Rhenish lignite mining region will primarily be used to supply the neighbouring conurbations in and around Cologne, Düsseldorf and the Ruhr region. A large share of the electricity generated could be used to produce hydrogen in Eastern Germany, which is more sparsely populated.

Germany’s biggest floating PV system is being set up on Cottbus‘ Eastern Lake, the largest artificial lake created on disused mining land in the region. An additional seven GW are planned in the region by 2040, two years after the scheduled end of mining work in Lusatia. Exploratory work is being performed at the Lusatian reference power plant (Link in German) to discover how hydrogen reconversion can be used to stabilise the grid.

Gas pipelines and cavern storage as a basis for hydrogen infrastructure

A further advantage is that the existing gas grid could be upgraded to transport hydrogen. A study commissioned by the Brandenburg Ministry of Economics (Link in German), in which the Fraunhofer IEG was also involved, revealed that such retrofits, combined with new pipelines bundled with these upgraded pipelines, could save about 55 percent of the costs that would be incurred for a complete new build. “Converting gas pipelines for hydrogen usage costs roughly two-thirds less than entirely new pipelines,” Ragwitz explains.

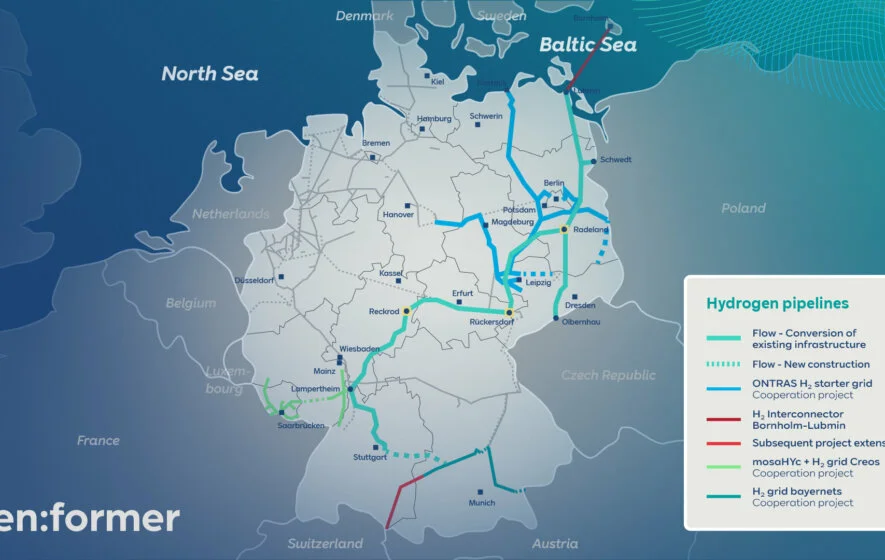

This is precisely what the nearly 30 partners of the consortium named ‘Flow – making hydrogen happen,’ to which RWE also belongs, intend to build on. Starting in 2025, they envisage converting 1,100 kilometres of gas pipelines from Lubmin in the northeastern-most point of the country to Stuttgart for hydrogen transport. The objective is to transmit hydrogen produced from wind farms in the Baltic Sea with a feed-in power of up to 20 GW across Germany to various industrial hubs.

Moreover, the planned pipeline will pass by large gas caverns in Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt and Hesse, which can be used as hydrogen silos. Large storage systems can act as buffers, while increasing security of supply year round.

Market players along all stages of the hydrogen economy

For example, the Flow lines could be used to supply hydrogen to the steel industry south of Berlin or to chemical and basic material sites in Leipzig and Leuna. Says Ragnitz, “Eastern Germany is thus a region that possesses the potential to cover the entire hydrogen value chain, from production to usage.”

In the middle of 2022, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the heads of government of the Eastern German states formulated and reached an agreement on the Baltic Sea island of Riems on goals and measures to develop the economies in the region in view of both current and future challenges such as the coronavirus pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the energy transition. This includes the construction of a hydrogen economy in Eastern Germany.

Apparently, German politicians share this view. In the middle of 2022, the heads of the administrations of the Eastern German states agreed with Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz in the Riems Declaration (Link in German) to form an “Eastern German hydrogen lobby”. Policymakers believe that the hydrogen economy represents an opportunity for the energy transition as well as for successful structural change, which will benefit the population and economy of Eastern Germany.