Easter – that time of year when the world seems to revolve around nothing but eggs. In Europe alone, the number of chicken eggs sold around the springtime festivities probably extends into the billions. And yet only a small proportion of the eggs produced each year is sold whole over the counter.

Eggs are not only used by the food industry for salads, mayonnaise or as a binding agent in convenience products. The manufacturing and pharmaceutical industries also rely heavily on the oval protein bombs. Half a million eggs are used every year to make flu vaccines alone, for example. Before now, the demand has been for the clear-golden contents. But recently, it is the shells that have been making the headlines.

Valuable waste resource

Egg shells contain a lot of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which is an important compound, used for a variety of purposes depending on its composition. So far it has found its primary use in the paper and construction industries, but it would seem as though CaCO3 is also the reason why constructors of electricity storage facilities are now eyeing up the egg shells.

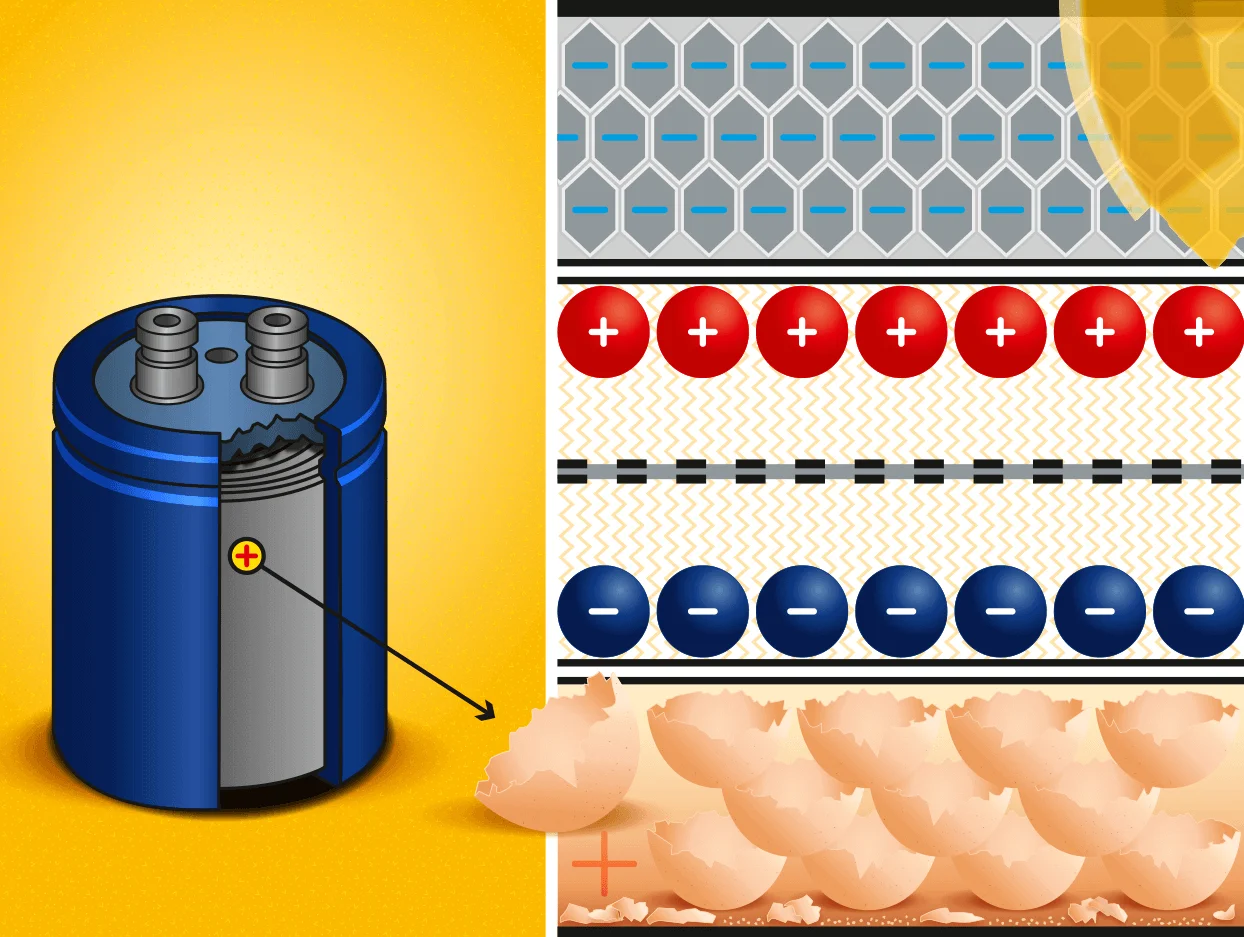

A German-Australian research group led by Manickam Minakshi of Murdoch University in Perth is responsible for the discovery. Having been involved in power storage facilities for years, Minakshi has now built a battery with an electrode made of egg shells.

To do this, the researchers ground up washed and dried egg shells to make a fine powder. They then processed the powder to make a foil which has been integrated into the rechargeable egg battery as a cathode as a counterpart to a lithium anode in a non-aqueous electrolyte. The result: “The cell maintained an excellent capacity of 92 percent over 1,000 charge and discharge cycles.”, was the conclusion of Minakshis’ research article, which Maximilian Fichtner of Helmholtz Institute Ulm (HIU) was also involved in.

Fundamental research is ongoing

Whether batteries with electrodes made of egg shells actually work in real life, is as of yet unclear. Currently, Minakshi and his colleagues are looking into ways in which to improve the capacity of the material. When questioned by en:former, Minakshi states, “Recently […] we found that heating the egg shell powder at different temperatures influences the storage capacity”.

According to Manakshi, industrial production not only has the potential to reduce the amount of bio-waste that is produced, it also has the potential to add considerable value to the renewable energy market. Although the rechargeable eggshell batteries are still a long way from mass production, Minakshi remains optimistic: “We are looking for potential partners, if anyone is interested, then we are happy to make a business plan.” At least the availability of the material shouldn’t be an issue…

Egg shells – too valuable to throw away

Pankaj Pancholi also believed that egg shells were too valuable to simply throw away. He processes around 1.5 million eggs per week in his food factory in Leicester, central England. And every week he has to dispose of more than 20 tons of eggshells. In 2016, he therefore decided to build a facility with which he could wash, dry and grind the egg shells. “We can produce egg shell powder in different degrees of granularity, which has been pasteurised and contains less than five percent protein,” he explains in an interview with en:former.

So far, however, Pancholi’s eggshell powder has been more of a passion project – “the story of my life” – he sighs into the phone. Because it, too, lacks marketing opportunities thus far. The powder is being explored in all kinds of projects – as a component in plastic compounds, concrete and asphalt. But it is in need of a business model: “For now, the facility has ground to a halt. I have more than eight tons of egg shell powder stockpiled,” Pankaj says, stressing that he is more than happy to send complimentary samples to anyone interested – and yes, even as far away as Australia.

The en:former team wishes you and your family a happy Easter. We thank you for your loyal readership and look forward to many more exciting articles and informative posts – sign up here for our newsletter. Stay en:formed!

Photo credits: Dmitry Galaganov, shutterstock.com; Nadiinko, shutterstock.com