Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rising energy bills have refocused energy strategy priorities on security of supply.

But, at the same time, European governments don’t want to lose sight of their net zero carbon by 2050 targets. As domestic electricity generators, renewable energy technologies, such as wind and solar, provide answers to both concerns.

As a result, governments are ramping up their renewable energy commitments, but also adopting different approaches to other technologies’ roles in the energy transition.

Domestic oil and gas

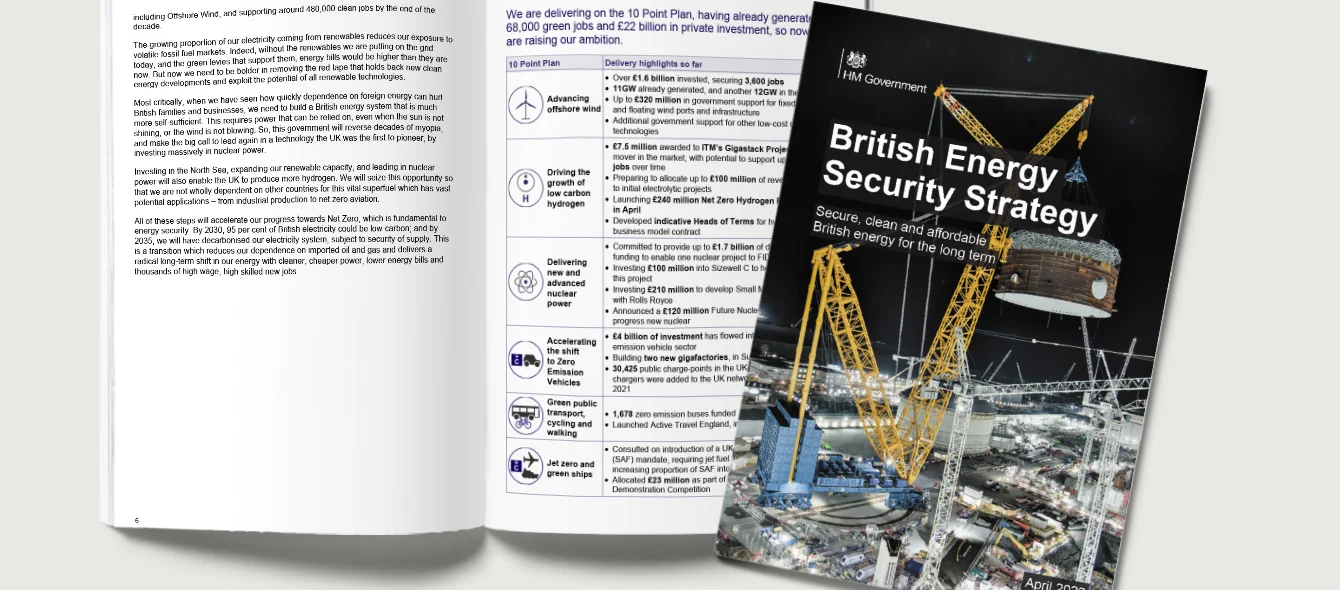

The UK’s new British Energy Security Strategy, published in April, involves a new lease of life for the North Sea, origin of the majority of the UK’s domestically-produced oil and gas.

Boosting oil and gas production may seem counterintuitive in terms of the energy transition, but the rationale is that some oil and gas use is unavoidable, especially in the short to medium term, and that domestically-produced fossil fuels provide greater security of supply than imported ones.

The argument is not universally accepted. Environmental organisations fear fossil fuel use will become locked into the UK energy system long-term, and that renewed fossil fuel spending will detract from investment in renewables.

The government argues that domestic production will sustain local jobs and should have lower greenhouse gas emissions, as the environmental standards used in extraction can be governed by the UK. In addition, North Sea oil and gas has less distance to travel to reach the consumer, which also helps limit its environmental impact versus long, international supply chains.

Fossil fuel consumption will still fall. By 2050, the government estimates the UK could be using a quarter of the natural gas it uses now, which would be decarbonized via carbon capture and storage.

More low carbon electricity, but onshore wind support limited

The government wants an acceleration of low carbon technologies, which will form the basis of both the UK’s future sustainability and its energy independence. The three primary generation technologies selected are offshore wind, solar and nuclear power.

According to the strategy, increased low carbon electricity generation will allow the electrification of transport and heating and the production of hydrogen, which the government sees as a “superfuel” capable of decarbonizing industry and aviation.

The strategy doubles the UK’s target for hydrogen production from 5 GW to 10 GW by 2030, subject to affordability and value for money.

The government also plans to blend up to 20% hydrogen directly into the existing gas grid in an effort to partially decarbonise natural gas use and provide a market for hydrogen producers.

The new energy strategy says that, by 2030, 95% of UK electricity generation could be low carbon, rising to a fully decarbonised electricity system by 2035, subject to security of supply.

For offshore wind, the already-ambitious 2030 target of 40 GW has been raised to 50 GW, including 5 GW of floating offshore wind, a technology designed to exploit wind resources in waters too deep for traditional fixed-bottom installations.

The first offshore floating wind farm, Hywind Scotland, was commissioned in 2017 and has regularly achieved the highest average capacity factor for offshore wind farms in the UK.

To achieve the new offshore wind target, the government promises to address one of the biggest challenges facing developers by reducing consent times from four years to one, as well as facilitating greater anticipatory investment in grid networks. It will also hold annual auctions for capacity, bringing forward the next one by one year to March 2023.

For onshore wind, the government does not include plans for wholesale changes to current planning regulations in England. While the pipeline of projects for onshore wind is relatively strong in Scotland and Wales, permitting issues have held up deployment around the UK. Onshore wind and solar are the cheapest forms of electricity generation in the UK, but onshore wind capacity increased by just 1 GW in the period 2019-2021.

The government anticipates up to a five-fold expansion in solar power by 2035 from 14 GW installed today. It will consult on amended planning rules to favour the development of unprotected, low-value or previously-developed land. It will also support the co-location of solar with other activities, such as agriculture, onshore wind generation or energy storage.

Both solar and onshore wind will be included in the government’s future contracts for difference auctions.

Betting big on nuclear

The energy strategy substantially increases the government’s nuclear ambitions. By 2050, it sees 25% of UK electricity being generated by nuclear power, up from 15% today.

The UK currently has six nuclear plants in operation, five of which will start decommissioning this decade. There is also one under construction, Hinkley Point C, the most recent cost estimate for which was £22-£23 billion. It is not expected to come online until at least 2026, later than originally planned.

Critics argue that nuclear power is very expensive and that given the existing fleet’s age, new reactors will not come into operation in time to make a meaningful contribution to the country’s low carbon generation.

The government’s strategy banks on 24 GW of nuclear by 2050, three times today’s capacity. The government wants one new project to reach a final investment decision (FID) by the end of this parliament, and two projects to reach FID during the next parliament, including Small Modular Reactors, an as yet untried technology.

Eventually, the government hopes to regain a technological lead in civilian nuclear power and reduce costs by building at scale, constructing one reactor a year, rather than one a decade.

Energy system development

Backing all of this will be the establishment of a Future Systems Operator to oversee the UK energy system. By the end of 2022, the government wants blueprints for the energy system’s long-term development.

The government will also ensure that Ofgem, the UK’s gas and electricity market regulator, speeds up its approval processes to build networks in anticipation of new sources of generation and demand. The government wants to reduce timelines for delivering strategic onshore transmission infrastructure by around three years.