Turning solar energy into electricity requires more than just intense solar radiation. Another factor is also crucial: having enough space. In fact, according to statistics from the Centre for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research Baden-Württemberg (ZSW), modern solar farms need around 1.4 hectares of land to accommodate each megawatt (MW) of production capacity. In other words: potential for expansion is limited. The good news, however, is that numerous concepts for dual land use are already being explored. In our solar series, we’ve already taken a look at a number of possible approaches – from solar canopies for motorways, to innovative integrated photovoltaic modules, to farms out on the open ocean.

All these concepts have one thing in common: they all rely on flat modules, oriented to face the sun. Germany’s TubeSolar AG, on the other hand, is trying a different approach. And for proof that the company is a spin-off from Munich-based photonics firm Osram, one need look no further than their innovative product. Instead of using PV modules with solar cells enclosed between two plates of glass, TubeSolar has designed its modules to be made of elongated glass tubes, which look deceptively similar to Osram’s fluorescent tubes. Reiner Egner, CEO at TubeSolar, explains the advantages of this design.

Mr. Egner, inserting PV cells into fluorescent tubes is an unusual choice. What prompted this approach?

Well, the physicist Dr. Vesselinka Petrova-Koch actually came up with the idea a few years ago. She approached Osram with a proposal to file for a patent and bring the invention to life, as a team. The plan was to repurpose the glass tube production facility at Osram’s site in Augsburg. So the bones of the applied technology originally came from Osram/Ledvance but, since we acquired the basic technology and patents, for example, they were taken over by TubeSolar AG as a result of the spin-off.

What sets your tubes apart from conventional PV modules?

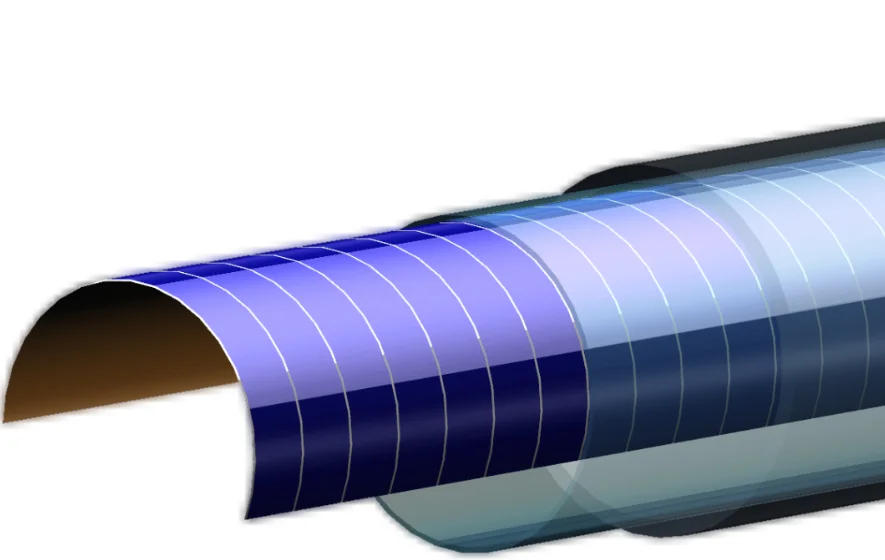

Our design relies on specially hardened glass tubes, making it innovative and unique. The glass tubes themselves are one metre long with a diameter of 2.5 centimetres and have integrated thin-film solar cells. A special fusion process is used to make the tubes airtight and watertight. The whole module then consists of two half-modules with 20 of these tubes connected to a bar. It’s one by two metres in size and weighs about 18 kilograms. The grid-like structure and its lightweight design mean we can install the modules just about anywhere, even eight or nine metres above the ground. So we think it’s likely to be a game-changer for agrophotovoltaics.

Speaking of agrophotovoltaics, this field – in particular – has already identified a number of concepts for enabling dual use of land. Bifacial modules with PV cells on both sides, for example, that can be installed vertically. What makes you confident the tubes can hold their own?

Bifacial modules are definitely a viable alternative – that goes without saying. But our tubes can actually be used to support plant growth. The tubes are set 2.5 centimetres apart, so 30 to 40 percent of the light shines through. This is particularly beneficial for growing certain plant species. In southern countries with much higher solar radiation, for example, this could be a real advantage. What’s more, our modules protect the ground below against hail and heavy rain. Thanks to the modules’ low wind load, they are very unlikely to sway, plus they are less demanding structurally. This lowers overall costs.

There are clearly many arguments in favour of the tubes. But what about their yield?

We are still in the process of optimising efficiency. The yield curve of our tubes is much more stable than that of conventional flat modules. This favours a higher overall yield. Due to their tubular design, the solar rays fall almost vertically on the cell foil for longer periods during the day. The tube shape also has a natural self-cleaning effect. The modules don’t get anywhere near as dirty as flat systems, which also has a positive impact on yield.

How much does this type of system cost?

Our production is semi-automated – for now. But, thanks to a grant of almost eleven million euros from the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, we are set to start highly automated production in late-2021. Initially we will have a capacity of 20 megawatts, but this will ramp up to 250 megawatts over subsequent steps. By scaling up, we’ll soon reach a point where we can compete with the high-quality crystalline modules currently available on the market – not least in terms of electricity production costs.

The first pilot projects are already in the works. Where are the plants going to be installed?

We’re currently planning pilot plants for the green roofs at the University of Applied Sciences in Weihenstephan and at a horticultural company, looking to combine our modules with plants that prefer partial shade.

It sounds as if those areas of application are worlds apart. What do you see as your biggest potential market moving forward?

Due to the advantages associated with dual use of increasingly scarce land, as I mentioned earlier, we will be targeting the agrophotovoltaics mega-trend. And, based on the fact that the energy is generated sustainably, we’re also looking at industrial and commercial roofs. In fact, the first German federal states have already passed laws, obliging commercial new-builds to include PV systems. The potential is huge: in Bavaria alone, we’re talking a serious number of gigawatts. Our systems are also the logical next step for green roofs – which are also gaining traction. In Germany alone, approximately seven million square metres of green roofing are installed annually. The lightweight design of our modules is less demanding in terms of structural engineering, and any vegetation under the modules can be maintained using machines. We’re confident that we can also tap this considerable market potential.