When early humans first lit fires, they had discovered controllable heat, even if their basic dwellings lacked modern accoutrements such as double glazing and insulation.

It was no mean achievement. Heating a home (or a cave) is not a luxury but a necessity, particularly for countries such as the UK, the most northerly points of which lie less than 500 miles from the Arctic circle.

Domestic resources

How heat is provided differs and very much reflects the immediate environment and available resources. In Scandinavia, where heat loads are higher, combined power and heat (CHP) systems, including district heating, are common.

CHP is efficient because it generates both heat and power at the same time, but such systems are rare in the UK, where heating requirements are substantial but less extreme.

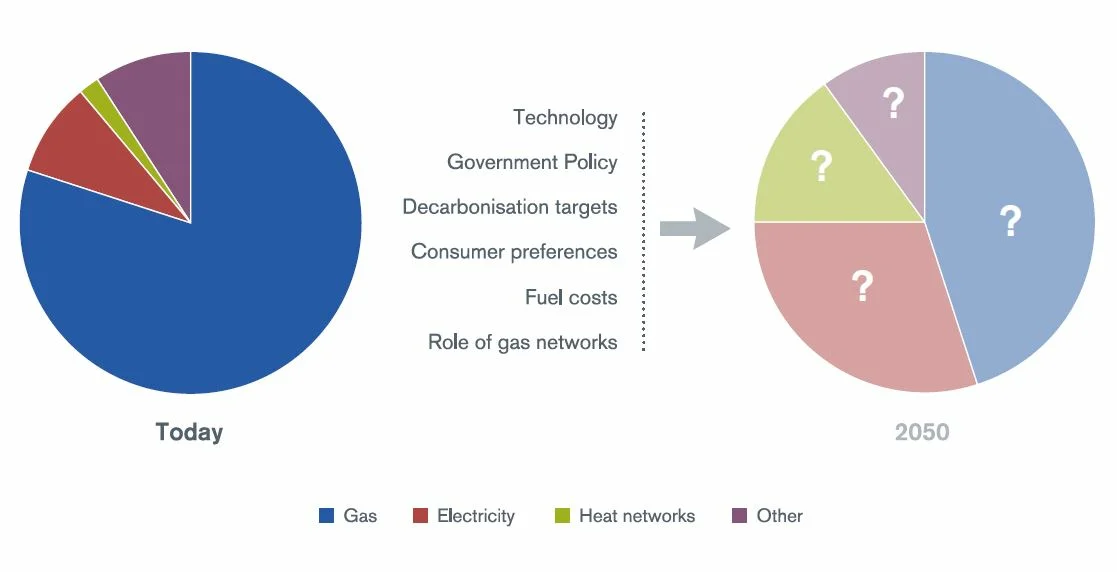

Instead, UK homes are heated primarily by domestic gas boilers – some 84% of UK homes have one. The use of natural gas stems from the discovery of oil and gas in the North Sea in the 1960s, which was given a major boost by the oil shock of 1973.

Natural gas provided a cleaner, domestically-produced home heating alternative to oil or coal, which had been restricted by the Clean Air Acts of the 1950s and 60s in order to eradicate the dense smogs that were enveloping the UK’s metropolises.

Green targets

Environmental concerns were a priority then, but have evolved considerably since, and attention has now focused on the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) generated by domestic gas use.

Domestic heat is estimated to account for 13% of the UK’s annual emissions footprint, but only 4.5% of the UK’s total heat demand in buildings is currently met by low carbon sources.

The government has set an ambitious economy-wide target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, which means decarbonization must be extended from the substantial gains made in the power sector to other major emitting areas such as heat and transport.

Change is already afoot. In Spring 2019, the UK government announced a ban on fossil fuel heating in new homes from 2025. In the Netherlands, which, like the UK, is a major natural gas producer, the government is taking action not just to ban new home gas connections, but disconnect some districts from the gas grid altogether. The proportion of Dutch homes with gas boilers is even higher than in the UK at 89%.

The scale of the problem is unquestionably big and not only in emissions terms.

According to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies report, Energy systems thinking and the decarbonisation of heat in the UK, peak heat demand in the UK is at least twice as high as current electricity demand, so while electric heating from renewable energy sources such as offshore wind or biomass are key parts of the solution, they are just two of the many elements likely to prove necessary in greening the UK’s heat.

Social costs

Given the essential nature of home heat, consumers are very sensitive to price and that applies not just to fuel costs, but the installation of heating equipment. Recognising the social need for heating, the UK government already applies a preferential rate of value-added tax to home heating fuels.

However, low carbon heat options have cost implications, and most homes are not new, and would have to be retrofitted with different technologies.

This raises the question of how the costs of a green heat transition should be borne, particularly for more vulnerable consumers who have invested in and are dependent on natural gas for warmth in their homes.

Greening home heat implies greater system integration as the energy world’s primary silos – oil for transport, gas for heat and a mix of generation sources for power – are broken down in the search for a sustainable low carbon energy system that encompasses all forms of energy demand.

It is from the synergies of system integration and sector coupling that many experts believe costs can be reduced.

Green Heat Roadmap

The UK government is currently devising a Green Heat Roadmap, which is likely to consider a number of possibilities to bridge the gap between the UK’s current use of natural gas in home heating and the emissions targets that have been adopted.

The government’s policy targets imply a wholesale change in the way the UK provides heat, one which the Committee on Climate Change says must start from the mid-2020s, if the net zero emissions by 2050 ambition is to be met.

There is no single, stand-out pathway to decarbonising heat in the same way that electric cars and buses can be seen as a solution for transport and renewables as a means of clean power generation.

The possibilities range from efficiency improvements, greater electrification to solar water heating, CHP where possible, ground source heat pumps, heat exchangers and the increased use of hydrogen and biogas within the natural gas system.

As such, the 2020s are likely to prove a decade of exploration and innovation in terms of both technology and policy to find the right pathway for heat decarbonisation.

Photo credits: Piotr Debowski, shutterstock.com