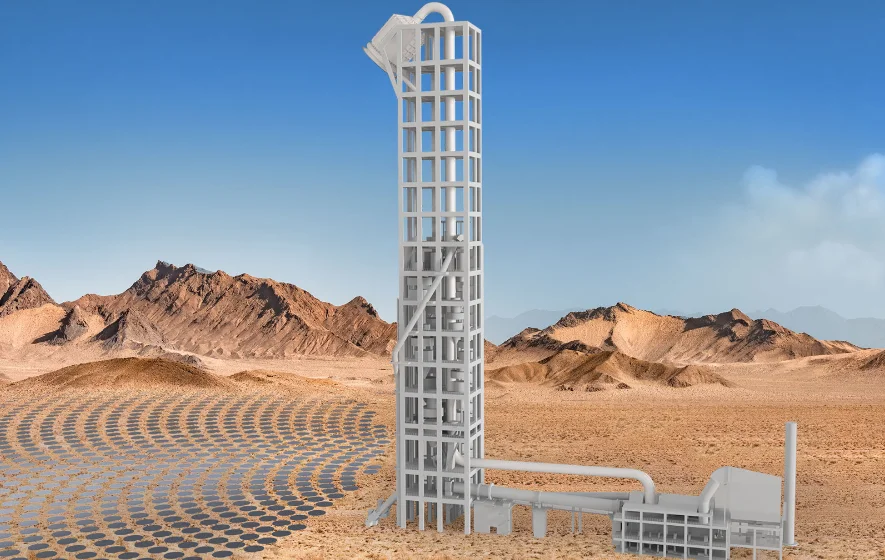

In Heidenheim, Württemberg, four European cement manufacturers are looking to develop a pilot plant to produce paraffin by 2023 – and the nearby Schwenk cement plant is to supply the necessary carbon. Mexican company CEMEX is pursuing a similar project: using technology from Swiss solar thermal company Synhelion, they are looking to build a completely carbon-neutral cement plant in Mexico by harvesting solar heat to supply energy. According to CEMEX, the necessary R&D has already been completed. A pilot plant is slated to go into operation next year.

Industry commits to Paris Agreement goals

To understand why the cement sector, of all industries, is focussing on saving or rather using CO2, one need look no further than its emissions. For they are considerable: in 2018, Germany’s cement industry was responsible for five percent of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. On a global scale, that figure rises to as much as eight percent. By way of comparison: aviation accounted for less than three per cent of global emissions in that same year.

Although the cement industry likes to highlight the long life cycle of buildings which use its product, most representatives also acknowledge that there is work yet to be done to reduce its emissions. Particularly if the sector wants to contribute to meeting the Paris Agreement targets. As a result, many companies have now pledged to do their bit. Three of the five largest cement companies in the world – HeidelbergCement, Swiss group LafargeHolcim and CEMEX – have all set themselves suitable emissions targets for 2030. And all three have their eye on becoming carbon-neutral by 2050.

In fact, many cement manufacturers have already taken steps to reduce their emissions. In Germany, for example, they emitted a solid 20 percent less carbon in 2018 than in the baseline year 1990. This may be a more modest reduction than the German average of 30 percent, but it is undoubtedly more than has been achieved in other sectors, such as transport.

Emissions based on chemical reactions

The second challenge facing the sector is a law of nature. The formula for the underlying chemical reaction is: CaCO3 à CaO + CO2. Calcium carbonate is turned into calcium oxide, i.e. cement clinker, which is the main ingredient in cement. Carbon dioxide is the inevitable by-product of this reaction, leading to the production of 60 per cent of emissions today. In other words: simply running the plants on renewable energy will do nothing to prevent the lion’s share of carbon emissions.

However, according to the German Cement Works Association (VDZ), this change, together with the introduction of more energy-efficient production processes, has allowed the cement industry to cut back on emissions. However, any further reductions achieved in this way will be severely limited, while meeting the goal of carbon neutrality will be nigh-on impossible. This is why the industry has set out to identify other ways to emit fewer greenhouse gases.

A greener energy mix

One approach taken by manufacturers is to reduce the proportion of high-emission clinker in the cement. Holcim Germany, for example, makes a cement in which oil shale replaces part of the clinker. According to the company, the CO2 emissions of this specific type of cement are 150 kilogrammes (kg) lower per tonne than those of conventional cement. By way of comparison: according to VDZ data, on average around 590 kg of CO2 was emitted per tonne of cement in Germany in 2018.

VDZ states that pre-calcined raw materials are suitable clinker substitutes. Fly ash from coal-fired power plants, slag from steel production, ground-granulated blast-furnace slag, and burnt clay are all technically possible options; potential limitations are mainly due to the availability of these materials.

Increase the recycling rate and efficiency

Another option is to recycle the concrete. However, fresh concrete manufacturing processes already have this covered, according to the InformationsZentrum Beton, and it merely leads to a conservation of raw materials. Recycling hardened concrete from demolished buildings, on the other hand, offers additional potential to cut back on carbon emissions.

Crushed concrete isn’t just a viable option for replacing building sand, which is now in short supply, it could also reduce the emissions associated with concrete. According to HeidelbergCement, over time, concrete absorbs an average of 20 per cent of the CO2 it has emitted previously. This is due to a process known as recarbonisation. And it does this of its own accord. However, special recycling methods are actually able to increase this percentage significantly, and a HeidelbergCement press release affirms: “This approach currently appears very promising.”

The plan: Recycle CO2 and use it as a raw material

Of course, what goes for all raw materials also goes for concrete and its key ingredient cement: efficiency is key. However, in view of growing global demand, this will have a limited impact. As things stand, it will only be possible to reduce emissions to zero if the CO2 produced is stored or recycled. However, CO2 storage is controversial, at least it is in Germany, where storing carbon in former natural gas caverns is a particularly contentious issue.

Using the CO2 is therefore considered a more sensible and potentially more lucrative approach. After all, greenhouse gas is a valuable resource for the chemical industry, e.g. in the production of plastics or for the synthesis of chemical energy sources such as natural gas, heating oil, diesel, petrol and paraffin. Although the CO2 is ultimately still emitted into the atmosphere when burned by the vehicles, at least it will have then been used twice. At the end of the day, halving greenhouse gas emissions in the two sectors would be a considerable step towards net zero.

Photo credit: shutterstock.com, Juan Enrique del Barrio