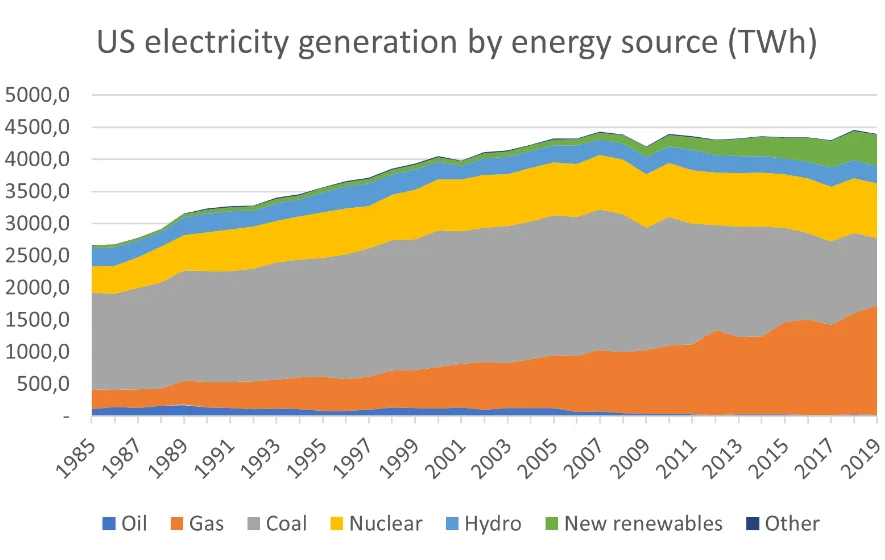

Coal has long been the mainstay of the US power system, providing more than 50% of total electricity generation for decades up until 2005. However, the US energy system is undergoing a huge transformation, driven by both policy and economics. Last year, coal accounted for just 23% of national power generation, less than half the level 14 years earlier.

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), 95 GW of coal-fired capacity closed or switched to an alternative fuel between 2011 and mid-2020. This is more capacity than most countries have across all energy sources. Moreover, a further 25 GW of US coal plant is expected to retire by 2025, by which time US coal-fired generating capacity will have shrunk by more than a third from its peak of 314 GW in 2011.

Drivers of change

Economics and policy are the driving forces behind this transformation. Shale gas extraction in the US has delivered huge quantities of gas at low and stable prices. This has boosted US exports of gas to Mexico by pipeline and as LNG by sea to multiple markets, including Europe.

But, at home, along with significant environmental opposition to new coal plant and more stringent air emission standards, which have added to coal plant construction and operating costs, shale gas has overturned coal’s traditional dominance as the cheapest fuel. Yet gas is not the only challenger. The adoption of renewable energy portfolio standards in many US states focused developers’ attention on clean energy sources. This has combined with the huge drop over the last decade in the cost of wind and utility scale solar power to give power plant developers a range of cheaper, cleaner alternatives to coal.

As a result, the pipeline of new coal plants under construction has come to a grinding halt. In 2019, the US built 23 GW of new power capacity, of which 39.6% was onshore wind, 36.1% gas-fired and 23.0% solar, leaving a paltry 1.3% — 300 MW – to all other energy sources.

Operational strategies

The new generation mix is changing how the remaining coal plant is operated. According to the EIA, in April and May this year, the coal fleet operated less than 30% of the time. Seasonal differences in utilisation rates have become more pronounced during the past two years as cheaper generation from gas and renewables pushes coal out. This means the US coal fleet is not only getting smaller, but what remains is being used less.

Lower utilisation has a big impact on the economic viability of existing coal plant and acts to hasten closures, particularly of older units. The average age at which coal plants are retired has been falling, dropping below 50 years in 2017 to average 46 years in 2018. As a result of the increasingly challenging economics, four large coal plants in the US have this year decided to operate on a seasonal basis only, i.e. to meet high winter demand from December to February and high summer demand from June to August. For the rest of the year, the plants will not operate at all.

No going back

Given alternative power sources which are both cheaper and cleaner, the decline of US coal-fired power generation is unlikely to be reversed.

In fact, there is every chance the transformation will gather pace as the US has yet to exploit its huge offshore wind resource and utilities are increasingly favouring renewables over both coal and natural gas.

With a stable policy framework in place, the US Department of Energy estimated last year that 22 GW of offshore wind could be installed by 2030 and 86 GW by 2050. Even this would barely scratch the surface of an estimated offshore power potential of more than 2,000 GW. In January, the EIA forecast that, this year, 42 GW of new capacity will be built, of which 44% will be wind and 32% solar, while gas-fired plant’s share will fall to 22%, with other technologies accounting for the remaining 2%.

Photo credit: shutterstock.com, visdia