In 2019, Germany’s hydroelectric power stations produced 20 terrawatt hours of electricity, corresponding to some 3.5 percent of the country’s gross electricity generation. Hydropower is the oldest technique for producing electricity from renewable sources, and it’s based on a very simple principle. Water is dammed up in lakes or against walls known as weirs. Then it’s channelled through a powerhouse where its kinetic energy drives a turbine that generates electricity.

The drawback of these power plants is that they interfere with the natural course of rivers. They disrupt the routes of migratory fish such as salmon and eel which swim upstream and downstream to spawn. This is why many run-of-river power plants are equipped with fish ladders and bypasses enabling fish to swim around the stations.

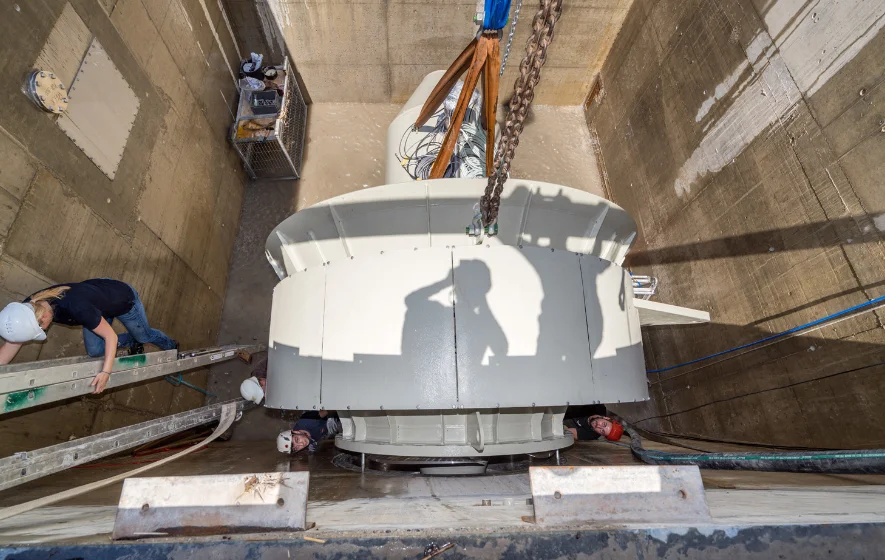

Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) are working on an alternate approach. A team of the Chair for Hydraulic Engineering and Water Management spearheaded by project director Prof. Peter Rutschmann has developed a hydroelectric power station that can be integrated into the riverbed. This shaft power plant allows fish to swim over it safely in both directions, while maintaining the banks and course of the river.

Constructing this new type of power station involves building a shaft extending from the weir to the riverbed into which the turbine and generator are integrated. The water flows into the shaft to drive the turbine. Only a small portion flows over it. Openings in the weir allow fish to migrate downstream unhindered. They overcome the height differential with ease. And they can navigate upstream via a fish ladder.

How the shaft power plant works

Shaft power plant

The hydroelectric power plant developed by TUM researchers generates electricity and is particularly fish-friendly. Discover the functions by clicking on the numbers.

Grating

In the shaft power plant, the grating lies horizontally above the turbine and prevents it from being damaged by debris.

Turbine

The turbine in the river bed generates electricity with the kinetic energy of the water.

Suction hose

Via the suction hose the water is led back into the river.

Height-adjustable closure

The height of the closure can be varied to drain off debris and high water.

Overflow

Water flows over the closure. This prevents turbulence and fish can simply swim over it.

Openings for fish exit

Openings in the weir allow fish to migrate downstream unhindered.

“You can’t see or hear the shaft power station. It’s so inconspicuous that we actually obtained a construction permit in a Natura 2000 area, a sanctuary for preserving endangered natural habitats,” says the scientist, who also conducts research in the test facility in Obernach, which is affiliated with TUM. Hydropower and flood protection are among the points of focus.

February saw the commissioning of a prototype shaft power plant in the Loisach river in Bavaria. It proved that this technology works in Alpine rivers with strong currents and large amounts of bedload.

“The critical component of a shaft power station is the grating,” the researcher explains. It extends over the turbine in the riverbed horizontally and acts like a filter that keeps the turbine from being damaged by debris. As the rod profile is y-shaped, it tapers off downwards. The gaps between the bars are 15 millimetres wide. Anything bigger than that is washed over the grating. It was built by Rosenheim-based Muhr, a company specialising in mechanical process engineering for hydroelectric power stations.

Fish swim over gratings

And that’s not all the innovative grating is capable of. Vertical diffusers arranged around conventional run-of-river power stations stop fish, branches and rocks from being swept into the turbine by the vortex it generates, which can be very strong. It is extremely difficult for small fish to pull themselves out of such vortices. The situation created by shaft power plants is different, as water flows into the shaft at a steady 0.3 metres per second without producing eddy currents. Rutschmann says, “It’s very easy for fish to cope with a grating this flat. All that’s needed from them to keep from getting caught between the bars is a slight adjustment in swim height, which is nearly effortless.”

The professor is convinced that the technology is also well-suited to other locations – not just on the merits of its strengths in terms of fish protection. “We can also build shaft power stations on existing dams, enabling us to preserve them,” he declares. Construction of a power plant near Bad Reichenhall is scheduled to start very soon. What stands out at this location is that it already has a historic concrete dam that is under a preservation order. It would be impossible to obtain a permit for a conventional run-of-river power station there, as the required modifications to the dam would be too extreme.

The 450 kilowatt (KW) rating of the shaft power plant in the Loisach river classifies it as a small station. But Rutschmann is optimistic about building such power plants of much bigger dimensions in the future. “The technology is similar to that of a wind turbine. The stations will incessantly increase in size,” he says, adding that construction costs will drop. Current projects have dual-purpose sheet pile walls: they retain water while also forming a shaft. In addition, prefabrication is being explored. This simplifies turbine installation considerably, thus reducing construction costs.

Pilot in NRW

A host of projects is being implemented at existing hydroelectric power stations as well. In one project, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia joined forces with RWE, the operator of the Unkelmühle hydropower plant on the Sieg, to make it fish-friendly. The station, which is rated at 420 KW, has been up and running since 1923. The pilot involved installing a bigger, extremely flat grating with bars spaced a mere ten millimetres apart. Now the water flows at through the grating at a maximum speed of 0.5 metres per second, enabling young fish to exit the area of their own accord. Moreover, the small gaps prevent them from being sucked into the turbine.

Experts involved in the project monitored fish migration in the Sieg very closely. They found that over 95 percent of the young salmon and up to 100 percent of the eel passed the power plant successfully. Electricity generation from the station dropped by between eight and 14 percent as a result of the retrofits.

Fishing eel out of the Mosel

Since 1995, the Rhineland-Palatinate State Environmental Agency, the SGD Nord approval authority and operator RWE have been pursuing a different strategy at the ten run-of-river power plants in the Mosel between Koblenz and Trier. As part of the eel protection initiative, professional fishermen are fishing silver eel, i.e. grown-up eel, out of the Mosel using fish traps and setting them free in the Rhine south of Koblenz. This enables the fish to continue their journey to the spawning area in Lake Sargasso in the Caribbean largely unimpeded by further hydropower plants. As a result, every year, the fishermen save up to 15,000 of these fish from being sucked into turbines. RWE forged a similar alliance to protect eel with the Ministry of the Environment and the Saar Fishing Association in Saarland in 2016. Concurrently, scientists are exploring additional ways to facilitate eel migration.

Photo credit: ©Frank Brecht / TUM