Europe’s electricity networks are not strong enough to make efficient use of regional excesses of renewable energy. Most importantly, the cross-border interconnectors do not rise to the tasks resulting from the energy transition. The second part of the Grid Expansion series demonstrates how adequate network expansion translates into increased security of supply, lower costs and less emissions.

The mission is clear: the European Union is aiming for at least nine out of ten kilowatt hours of electricity to be generated from renewables by around 2050. What is also clear, however, is that this will only work if everyone pulls together. Or, perhaps more fittingly, if everyone is connected to the same grid.

After all, the main sources of renewable energy – the wind and the sun – do not cater to the needs of consumers. It should be possible to provide a fairly steady supply of green electricity if system load were balanced across regions and national borders. As the saying goes, whenever the wind blows, the sun is shining somewhere else. And, the larger the interconnected area, the more likely it is that electricity supply is guaranteed.

But is this hypothesis correct? This is what the German Weather Service examined. Experts looked into how often wind turbines and solar panels produced less than ten percent of their rated output (their operationally optimised peak output) over a period of 48 hours between 1995 and 2015 due to the weather. The study, which was published in early 2018, demonstrates that this happened twice a year in Germany. In Europe, however, such a shortage was witnessed just once during the ten-year horizon.

That sounds promising. But, as of yet, Europe’s transmission grids are not suitable for transporting the required amounts of electricity. There is thus an urgent need for a powerful European transmission network. According to a an investigation carried out by the Technical University of Munich (TUM) this could increase the share of electricity supply accounted for by wind and solar power from 60 percent to over 85 percent.

EU plans for the open electricity market

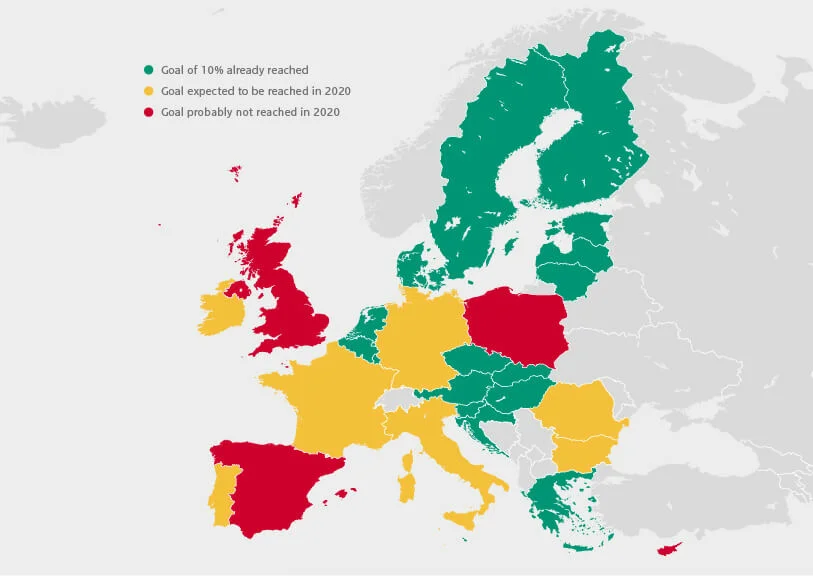

In 2015, the European Union established the goal to network all members states via cross-border interconnectors by 2020, enabling at least ten percent of the capacity installed there to be transmitted to other countries. Landlocked EU countries already satisfied this requirement back then. Only insular and peninsular member states such as the United Kingdom and Spain as well as countries on the EU’s eastern border fell short of this threshold value: Romania, Poland and the Baltic states.

However, enough interconnectors only pay half the rent. This is made apparent by the situation in Germany: In the north, wind turbine output has to be reduced time and again during high wind speeds, because the electricity they generate cannot be transmitted fast enough to the south. It is impossible to do this within Germany or via neighbouring countries, although suitable interconnectors exist for example in the Benelux nations. However, when in doubt, neighbours close off their interconnectors in order to protect their transmission networks from being overloaded.

We are thus a far cry from meeting the EU Commission’s ambition of fully tapping the potential of renewables by enabling energy within the European Union to flow “without any technical or regulatory barriers”. In fact, we are miles away from this scenario.

110 EU-subsidised projects for the electricity sector

At least things are moving. The UK alone plans to increase the capacity of its cross-border power lines from four gigawatts (GW) at present to 11.7 GW. Today, the United Kingdom is connected with Ireland, France and the Netherlands. It is envisaged that such interconnectors be built to Norway, Denmark, Germany and Belgium by 2022.

If London has estimated UK electricity demand in 2025 correctly, the country alone could then import more than one-fifth of the electricity it needs. This is the calculation performed by The Guardian. Additional interconnectors are also being debated, including one to Iceland.

And the United Kingdom is not the only nation taking concrete action. By 2030, all EU member states are to be able to export 15 percent of their generation capacity. A vast number of high and ultrahigh-voltage lines are being built and planned throughout the European Union. A list published in 2017 contains 110 network expansion projects including several smart grids.

Expansion probably the cheaper option

All of this will cost a lot of money. The European Commission estimates the required investment to total 140 billion euros between 2014 and 2020 alone. In a study entitled ‘Completing the Map’ the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity ENTSO-E actually predicts that 12 billion euros will have to be invested every year through to 2040.

However, it will probably be even more costly to be idle. Another calculation by the experts: idleness will cost three times more. The aforementioned analysis by the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the ENTSO-E study make the same assessment – for obvious reasons: Barring appropriate connections, conventional power stations have to be ramped up in one country while its neighbour limits the output of its wind turbines and solar panels or actually ‘destroys’ electricity.

According to ENTSO-E, this means an amount of electricity equal to annual consumption in the Benelux states could end up ‘on the rubbish heap’ in the EU in 2040. Moreover, electricity on one side of the birder could cost six times as much as on the other.

Increased competition for lower electricity prices

To prevent this, the Network suggests building 166 lines and 15 large-scale storage facilities by 2030 alone, at an investment cost of 114 billion euros. ENTSO-E estimates that annual average savings through to 2030 will amount to between 2 and 5 billion euros.

According to the TUM study, such measures would not just benefit operators of renewable power generation plants. If renewable electricity feed-ins fluctuated less throughout the greater catchment area, conventional power stations could run more consistently and more frequently under full load – and thus more efficiently.

A nice side effect is that improving the physical handling of electricity would increase competition among power producers throughout the EU. Furthermore, the more providers compete against each other, the more likely they are to be compelled to pass their cost advantages on to consumers.

In the ‘Grid Expansion’ series, en:former provides insight into technical, societal and economic challenges as well as initiatives and innovations for overcoming them. The next part of the series will be dedicated to the bureaucratic, technical and social hurdles in the way of expanding grids rapidly and the measures policymakers intend to take to overcome them. Afterwards, en:former will present some technical approaches to accelerating network expansion.

Photo credits: Comaniciu Dan, shutterstock.com