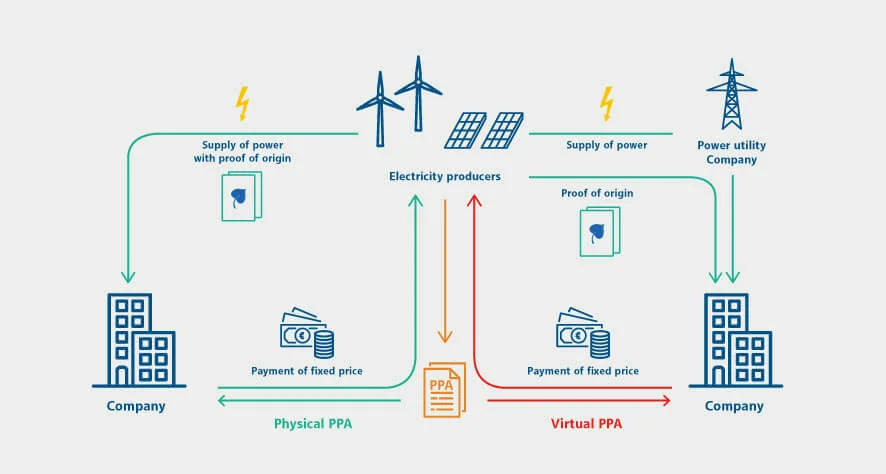

In other countries, they have long formed the financial backbone of the energy transition: power purchase agreements (PPAs). On principle, they are nothing but (at least long-term) supply contracts between generators and buyers of electricity. For instance, they stipulate that the user purchases all of a plant’s electricity (or at least a large portion of it) at a fixed price. The terms of such agreements vary, with 15 years being customary for new stations.

This type of contract enables both parties to make reliable plans. On the one hand, the power consumer is not exposed to fluctuating exchange prices. On the other hand, the producer knows from the outset that it will not be ‘stuck’ with its electricity or its generation capacity. Besides securing revenue, it reduces the operator’s cost of capital. As a permanent employment contract serves as collateral for a private mortgage, so does a PPA for banks and other creditors. After all, the more certain it is that a borrower will pay its instalments on time, the lower the interest rate.

Major impact on wind and solar power

PPAs are nothing new and are used in a similar way to finance conventional power stations. However, they are particularly important when it comes to building wind and solar farms.

There are two reasons for this. Electricity produced from these energy sources has next to no unit costs. In other words, operating costs are virtually independent of capacity utilisation. It always costs the same to run these plants – no matter how much power they produce. Unlike power stations, which require fuel, every kilowatt hour of electricity generated is thus profitable – or at least reduces loses. Their operating costs are thus largely independent of commodity prices. This allows them to be forecast accurately and calculated when negotiating a PPA.

However, wind and solar farms depend on the weather. They cannot generate electricity on demand – especially not when it would be particularly profitable to do so. After all, the higher the share of the electricity mix accounted for by renewables, the faster the price of electricity falls whenever the wind blows or the sun shines. This is because the competition also produces full tilt during such periods, resulting in a latent oversupply, which drives down short-term exchange prices.

PPAs allow for green power without subsidies

In the long run, highly predictable costs combined with a fixed purchase price result in highly predictable risks, which offset changes in weather and – in turn – production.

This is why PPAs make investing in wind turbines and solar panel arrays attractive even without state subsidies. Case in point: the Don Rodrigo solar farm engineered and built by BayWa r.e. in the south of Spain. The Bavarians announced that all systems were “go” in April 2018, having concluded a 15-year PPA. Norwegian energy group Statkraft will buy the roughly 300 gigawatt hours in annual generation to supply some 93,000 homes in Greater Seville. At the end of 2018, BayWa r.e. announced the completion of the facility, consisting of approximately 500,000 PV modules. Early June will see BayWa r.e. constructing the first unsubsidised solar farm in Germany with plans to secure financing via a PPA once again.

PPA boom in Germany after 20 years of the Renewable Energy Act

So far, PPAs have played a minor role in Germany because investor returns are secured for the first 20 years of operation via the feed-in payments under the Renewable Energy Act (REA). However, the oldest wind and solar farms will soon have been running for 20 years given that the REA entered into force in March 2000.

Experts thus predict a veritable PPA boom starting in 2020 – primarily for wind turbines. After all, by and large, operators will have two options after the first 20 years. Ideally, Germany’s current Building Use Regulation will allow for a new, more powerful installation to be set up at the same location. Besides accelerating the energy transition, this would also enable the operators to secure the REA apportionments for another 20 years, provided that they have won a tender in an auction.

However, forecasts deem two-thirds of the current sites unfit for repowering, one reason being that the old plants are located too close to homes according to current approval practices. Operators may look for PPA partners to ensure that existing facilities continue to generate electricity profitably. This will likely be a prerequisite for follow-up financing for many of them. PPAs would definitely give them planning certainty, allowing them to cover maintenance costs.