They account for a mere two to three percent of a wind turbine’s weight. However, rotor blades pose the biggest challenge as they approach the end of their service life. Scientists from myriad sectors are working on solutions today in order to prevent this from being a problem five years from now.

And this is absolutely necessary, as various estimates have up to 14,000 wind turbines being decommissioned in western and central Europe by 2025. This is because the first wind energy boom started at the turn of the millennium and wind turbines are designed to run for 20 to 25 years.

Established disposal routes

Some turbines that have been taken out of service are sold in other countries where they produce electricity a couple of years longer. This works quite well especially when intact turbines in Germany are replaced by more powerful ones, a process referred to as ‘repowering’. However, this ‘second life’ solution becomes increasingly complicated and in some cases unprofitable as wind turbine size and sophistication rise.

So going forward, operators will have to dispose of thousands of wind turbines every year in order to comply with building regulations. By and large, this is not problematic as most components can be reused or recycled on veritable second-hand markets.

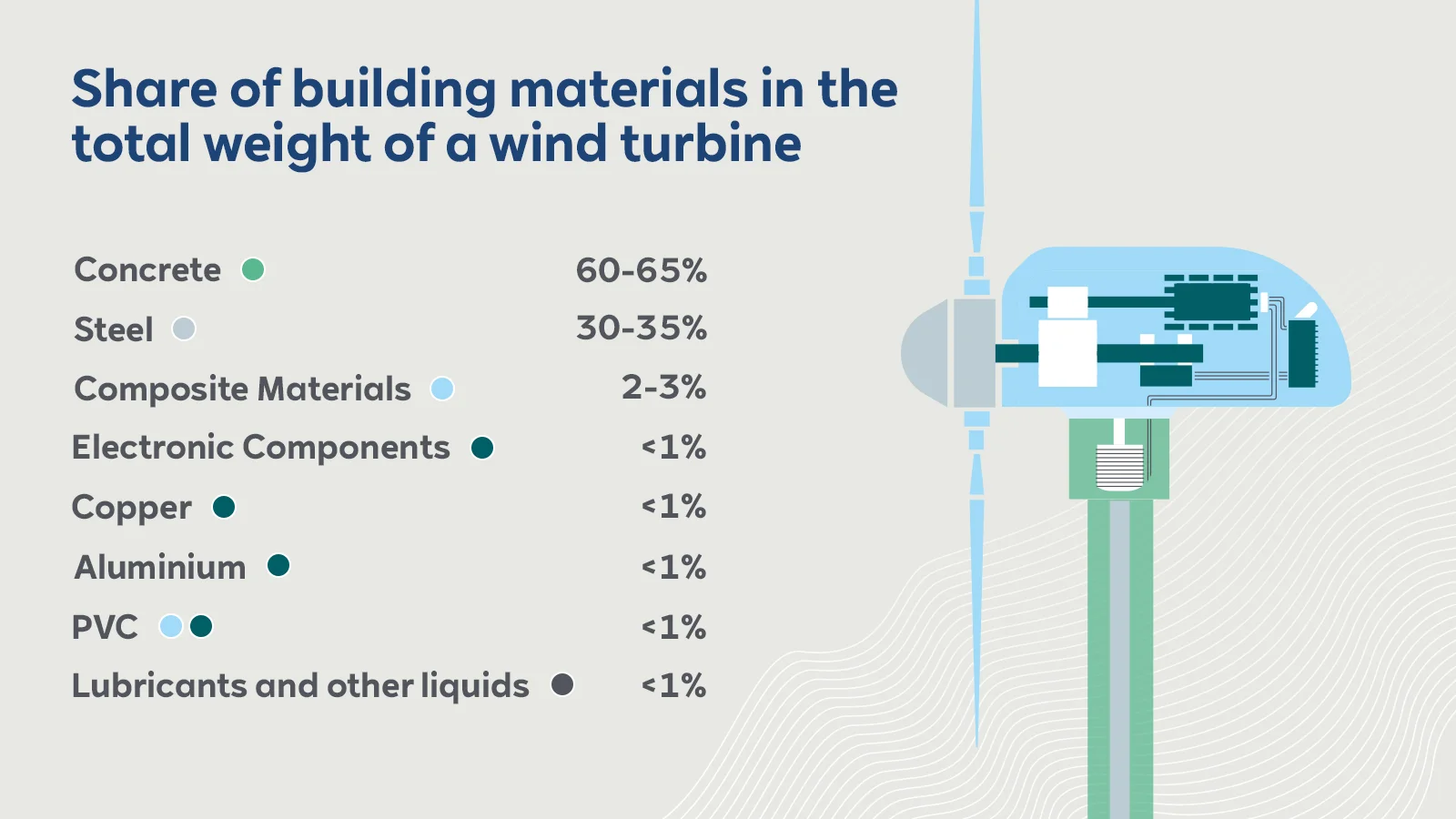

The foundation and tower alone make up 90 percent of a wind turbine’s weight. They consist of a two-thirds to one-third mix of concrete and steel. Added to this are mechanical and electrical components, i.e. the turbine in the nacelle and the transformer station on the ground. They are mostly made from various metals, PVC and lubricants. Non-recycled parts can be used as fuel for energy in waste incineration plants.

The composite material conundrum

What remains are fibreglass and carbon fibre-reinforced plastics (FGRP & CFRP) – the materials of which the wind turbine rotors and nacelle are made. The components of these composites are bonded together with synthetic resin so firmly that – if at all – they can only be separated from one another by taking extreme measures.

The problem has long been known. After all, airplanes and automobiles are increasingly made of extremely lightweight, but very stable plastics. However, for many years, the composite share was much too small for companies to be interested in developing solutions to reuse or recycle them. The consequence: They were simply dumped on landfills.

This is changing commensurate to the rising amount of composite waste. In view of the hundreds and thousands of tons that will soon be amassed every year in the wind energy industry alone, scientists are developing increasingly effective processes for dissolving the purportedly perpetual bonds.

New recycling market on the rise

Bremen-based waste management company neocomp has already established a method for dealing with FGRP rotors. They are cut into pieces on site and shredded in a specialised facility. What remains after weeding out the metal parts is a granulate that can be used to generate electricity in the energy-intensive cement industry.

Moreover, the residual glass ash can be used as a substitute for silicate or raw sand. To quote a background paper by the German Wind Energy Association (BWE), “This way, the use of 1,000 metric tons of old FGRP (sic!) can result in savings of about 450 metric tons of coal, 200 metric tons of chalk and 200 metric tons of sand.”

Conserving even more energy

However, physicist Peter Meinlschmidt of the Fraunhofer Institute for Wood Research is intent on extracting even more from the rotor blades – literally. “In many models, the GFRP structure is reinforced with balsa wood,” he explains to en:former. This tropical wood, which is used in model construction among other things, is much too valuable to be burned, says Meinlschmidt. And not just because its calorific value is nearly zero due to its low density.

The researcher goes on to say that it is much better suited for use in thermal insulation applications. He has thus developed a process that extracts the wood from the shredded rotor blades. “We have come up with a series of products that could be used to insulate buildings,” Meinlschmidt declares. “This ensures increased energy savings through recycling, in the spirit of the energy transition.”

Desired endgame: waste-free wind turbines

However to date, the aforementioned methods have only worked using fibreglass. Composites including carbon fibre render the undertaking more difficult. The reason sounds banal: Carbon fibre conducts electricity and can thus cause shredders and incineration plants to short-circuit. According to the German Wind Energy Association, despite this, at least two companies are already specialised in finding ways to take this hurdle as well.

The sector’s objective is clear: make wind turbines fully recyclable or reusable. In January 2020, Vestas, the world market leader from Denmark, announced that it would manufacture ‘zero-waste’ turbines starting in 2040. In February, the European sector association WindEurope declared this goal an important task, adding that a cross-sector alliance consisting of WindEurope and the European Chemical Industry Council Cefic and the European Composites Industry Association EuCIA is working on this.

At the end of November, the German Environment Agency expressed its fear of the country approaching a bottleneck in FGRP/CFRP component recycling if these materials reached a volume of up to 70,000 metric tons by 2040. The German Wind Energy Association has a different view, claiming that the crusher in Bremen has an annual capacity of 120,000 metric tons, which would suffice to handle the disposal of German wind turbines for the time being.

Video: Dismantling and recycling of wind turbines (EnergieAgentur.NRW)

Photo credit: shutterstock.com, lusia83