Solar energy – power of the sun for clean energy

150 million kilometres away, 109 times as big as our Earth, 70 percent pure hydrogen – we’re talking about the sun. Despite the sheer unimaginable distance travelled, the amount of sunlight that hits the earth’s surface in one and a half hours is enough to supply the entire human race with enough electricity to last a whole year. Solar energy, which can be used in the form of electricity, heat or chemical energy, therefore harbours enormous potential. It is already being used around the world and is becoming increasingly integral to energy supply.

The power of the sun can be harnessed in two ways to generate electricity. In photovoltaics (PV), the sun’s radiation is converted directly into electrical energy. The solar cells consist of a semiconductor material, which sets electrons in motion under the influence of sunlight, thereby generating electricity. When it comes to solar thermal energy on the other hand, solar radiation is concentrated with the help of mirrors. This resulting heat is first used to generate steam, which then drives a generator via turbines to produce electricity.

Solar PV: The most cost-effective way to produce electricity

Solar PV has two advantages: solar cells are manufactured in large factories, allowing for significant economies of scale. Correspondingly, manufacturing costs have fallen considerably in recent years, with the result that, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), solar PV, subject to suitable locations and the right framework conditions, has become the cheapest form of electricity generation. What’s more, the modular technology can be used in small units, enabling a wide range of applications, such as installations on the roofs of factory and residential buildings or as large ground-mounted systems.

Share of solar energy in electricity production in 2020

Current articles on the topic of solar energy

Considerable growth for years to come

In 2019, solar PV energy accounted for just less than three per cent of global electricity supply. This share will increase significantly in the coming years. For, according to IEA estimates, by 2030 wind turbines and solar farms will make up around 80 per cent of newly installed capacity. As a result, solar PV capacity is set to expand by an average of 12 percent per year. Thanks to this growth, renewables could replace coal as the most important energy source in power generation worldwide by 2025.

Solar energy with huge potential

On rooftops, above farmland or floating on a lake: solar energyAuf dem Dach, über Feldern oder schwimmend auf Seen: Solar energy offers numerous different applications and new, innovative alternative implementations are constantly being added. Today, solar modules are already generating sustainable electricity in a wide variety of applications. A selection can be found here:

PV technology: From satellites to rooftops

The solar cell was first used in the 1960s for space travel. Its job was to supply a satellite with electricity. Since then, PV technology has come along leaps and bounds. In the past ten years alone, costs have dropped by around 90 percent with the result that solar systems are being set up in their millions. The installations are finding their way onto rooftops or are being mounted on the ground, meaning solar energy’s share of the electricity supply is only set to keep on growing.

More power with ground-mounted systems

Ground-mounted systems generate electricity much more cost-effectively than rooftop PV as they are usually many times more powerful and easier to install. In densely populated areas such as Western and Central Europe, however, solar energy has been forced to compete with other industries.

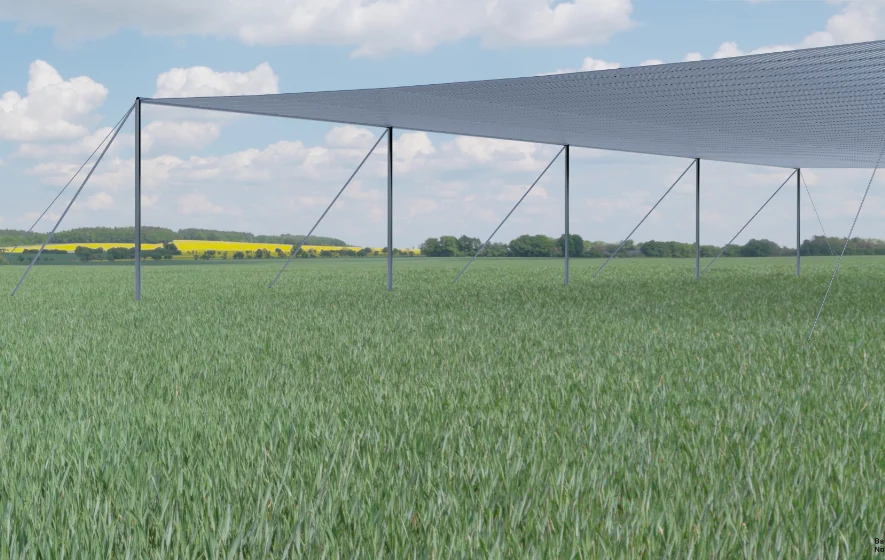

Agrivoltaics: Solar farm and field in one

One possible solution is something known as agrivoltaics, i.e. co-developing land for agriculture and solar energy. One approach sees solar modules installed high above farmland. Another relies on vertically mounted, bifacial solar cells that can be used to produce electricity on both their front and back sides, making them particularly compact.

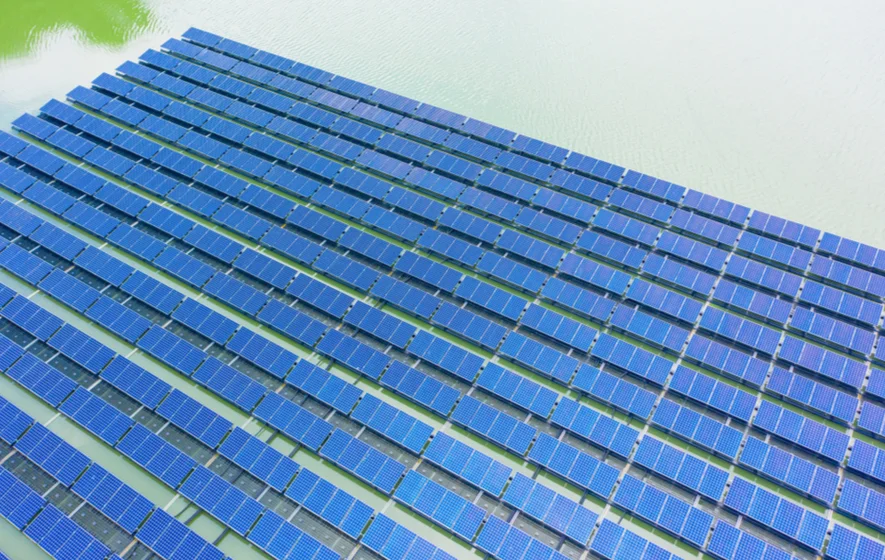

Floating solar modules

Another innovative solution for efficient land use is floating solar. Floating solar farms on lakes and off the coast can open up new areas for solar energy and yield more electricity than their land-based counterparts – because the water cools the systems, increasing their efficiency.

Solar modules to replace roofs or be used over highways

In addition to agrivoltaics and floating solar, scientists and companies are developing other novel applications for photovoltaic technology. When it comes to in-roof PV systems, rather than being attached to roofs, solar modules now serve as the roof covering itself. Another approach is huge transparent solar roofs which could one day make large stretches of motorway or dual carriageway usable for solar power generation.

Producing electricity at night with solar thermal energy

Compared to photovoltaics, solar thermal power plants require significantly more direct sunlight to generate electricity efficiently. The stations do not convert the sun’s rays into electricity directly, but rather concentrate the rays to generate heat. This heat is used to produce steam, which then drives a generator via turbines – not unlike conventional power plants. This gives solar thermal an advantage. Given that the heat can be stored for several hours, the power plant can also produce electricity when the sun is not shining.

Areas with high solar radiation and hours of sunshine aplenty could be potential sites for solar thermal power. Large stations are located, for example, in the south of Spain, in California and on the Arabian Peninsula. The prices associated with electricity production from solar thermal energy are generally higher than those of PV and wind. However, they have fallen in recent years. New projects in Australia, Chile and the United Arab Emirates, among others, are also in the works.