“Norway is our most important energy supplier today and should remain so on the way to a carbon-neutral future,” said German Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Robert Habeck, when he visited the Norwegian Prime Minister, Jonas Gahr Støre, in Oslo in January.

Not only is the Scandinavian country an attractive ally as Europe’s biggest gas producer after Russia, a geopolitical partner, and one of the most stable democracies in the world, but the country has also been deploying carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology since 1996.

In Norway, carbon dioxide from energy generation and industrial processes is captured, liquefied and buried permanently under the North Sea. Although this is not the only way to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, it is currently the most economical, making it the method of choice for dealing with emissions in industries where greenhouse gasses are an inevitable by-product, or can only be avoided with great effort.

Carbon neutrality is considered unachievable unless technologies are employed to capture CO2 emissions, preventing them from entering the atmosphere. The permanent storage of gasses is referred to as CCS; if it is used for downstream chemical processes, it is called CCU (Carbon Capture and Usage). A number of studies have even shown that it will be impossible to hit the Paris climate targets unless we capture carbon and remove it from the atmosphere using CCUS techniques.]

In Germany, however, these technologies are not without controversy. While Vice-Chancellor Habeck acknowledges, “carbon dioxide is better in the ground than in the atmosphere” and although concerns about environmental risks have lessened over time, CCS is still not permitted in Germany. However, German greenhouse gasses could be stored in the Norwegian seabed.

For this to be possible, the London Protocol on Marine Protection would first have to be amended, although this is seen as something of a formality. The question is rather what CO2 price would have to be set for the process to become financially viable for companies. The European Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) is the main economic incentive for companies looking to reduce their emissions.

Heidelberg Materials invests in low-emission cement production

When all is said and done, CCS will most likely be unavoidable for processes where greenhouse gases are an inevitable by-product. The best example of this is cement production, which accounts for around eight percent of global CO2 emissions. The carbon dioxide here is a by-product of the chemical reaction that produces cement clinker.

Nevertheless, cement producers are also committed to the Paris climate goals. German industry leader HeidelbergCement has set its sights on becoming carbon neutral by no later than 2050. To this end, its subsidiary Norcem’s plant in Brevik on the Norwegian southeast coast is currently being fitted with a CO2 separator – which the company says is the world’s first industrial CCS system within a cement plant. From 2024 onwards, an annual 400,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide are to be filtered out of the flue gases emitted during manufacturing and permanently stored in the North Sea.

Equinor and RWE plan to build a hydrogen economy

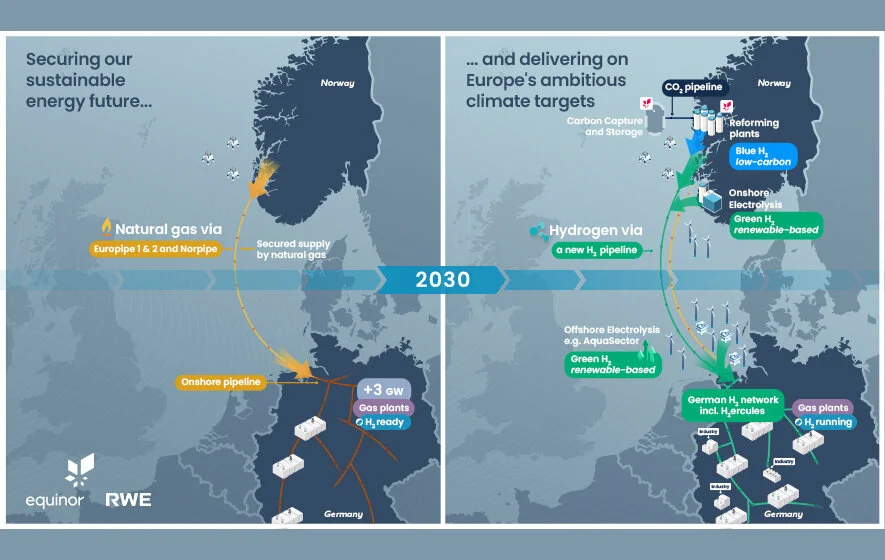

But Norway has more to offer than just CO2 storage. During Minister Habeck’s delegation trip, the CEOs of two energy companies helped pave the way to achieving carbon neutrality. Anders Opedal of Norway’s state-owned Equinor and Markus Krebber of RWE signed a memorandum of understanding in Oslo, agreeing to codevelop a hydrogen economy on both sides of the North Sea.

The memorandum envisages several interlocking areas of cooperation. First, there is the construction of several combined-cycle gas turbine power plants in Germany. At a total capacity of 3 gigawatts (GW), from 2030 they will be used to close potential supply gaps from temporary wind and solar power shortages. And the best bit: the power plants will be H2-capable. In other words, they can be fuelled with natural gas as well as hydrogen to generate energy.

First natural gas, then blue, then green hydrogen

At first, the power plants will be fired with natural gas and then, supplies permitting, they will be converted to run on clean hydrogen. Initially, this will probably be what is known as blue hydrogen from Norway. The molecule is produced using natural gas, but more than 95 percent of the carbon dioxide emitted is prevented from entering the atmosphere through CCS. The necessary 2 GW of production capacity are to be built in Norway by 2030, with up to 8 GW to be added by 2038.

To transport the clean hydrogen from Norway to Germany, a consortium led by Equinor and state-owned gas grid operator Gassco is currently looking into building an H2 pipeline through the North Sea.

Gradually, more and more power plants are to be converted to run on green hydrogen. Norway, which is known for its hydropower, is considered an obvious choice for sustainable electrolysis.

The AquaSector project, which has already been launched by Equinor and RWE, is to provide another source of green hydrogen. The offshore wind farm boasts 300 MW of installed capacity, which will be used to drive electrolysers that will also be built at sea. According to information from the AquaVentus umbrella project, not only does offshore electrolysis promise considerable time and cost advantages: Hydrogen pipelines also have a significantly lower impact on the sensitive ecosystem of the Wadden Sea compared to electricity cables with similar capacity.